America's Childcare System Is Broken. Bringing Back The Program We Used During WWII Could Fix It.

The 1940 Lanham Act provided universal, low-cost childcare during the War. Then, it was taken away.

This article is for paying JoeWrote readers. This week only, you can become a paying subscriber for 50% off! That gets you access to premium articles (like this one), bonus content, and supports my work, all for half-off. Don’t miss out!

Thank you for your support, and enjoy! - Joe

A quick Google search of “leave a child home to work” provides a depressing glimpse into the state of American childcare. The top results are all keyword-targeted articles, answering the common questions of American parents. “Is it illegal to leave my child alone? I have to go to work.” “How long can a kid be left alone?” And, most depressingly, “Will my child be safe if I leave them alone?”

These aren’t the ponderings of neglectful parents, but rather the consequence of our for-profit economic system. Under Capitalism, working-class parents must work enough to feed their families. This raises the obvious question, “Who is watching the kids while the parents are working?” This isn’t much of an issue for high-paid workers, as one parent can earn more than enough to provide for the family, while the other stays home and tends to the children. Or, if they’d rather pursue dual income, then they can hire a nanny or caretaker.

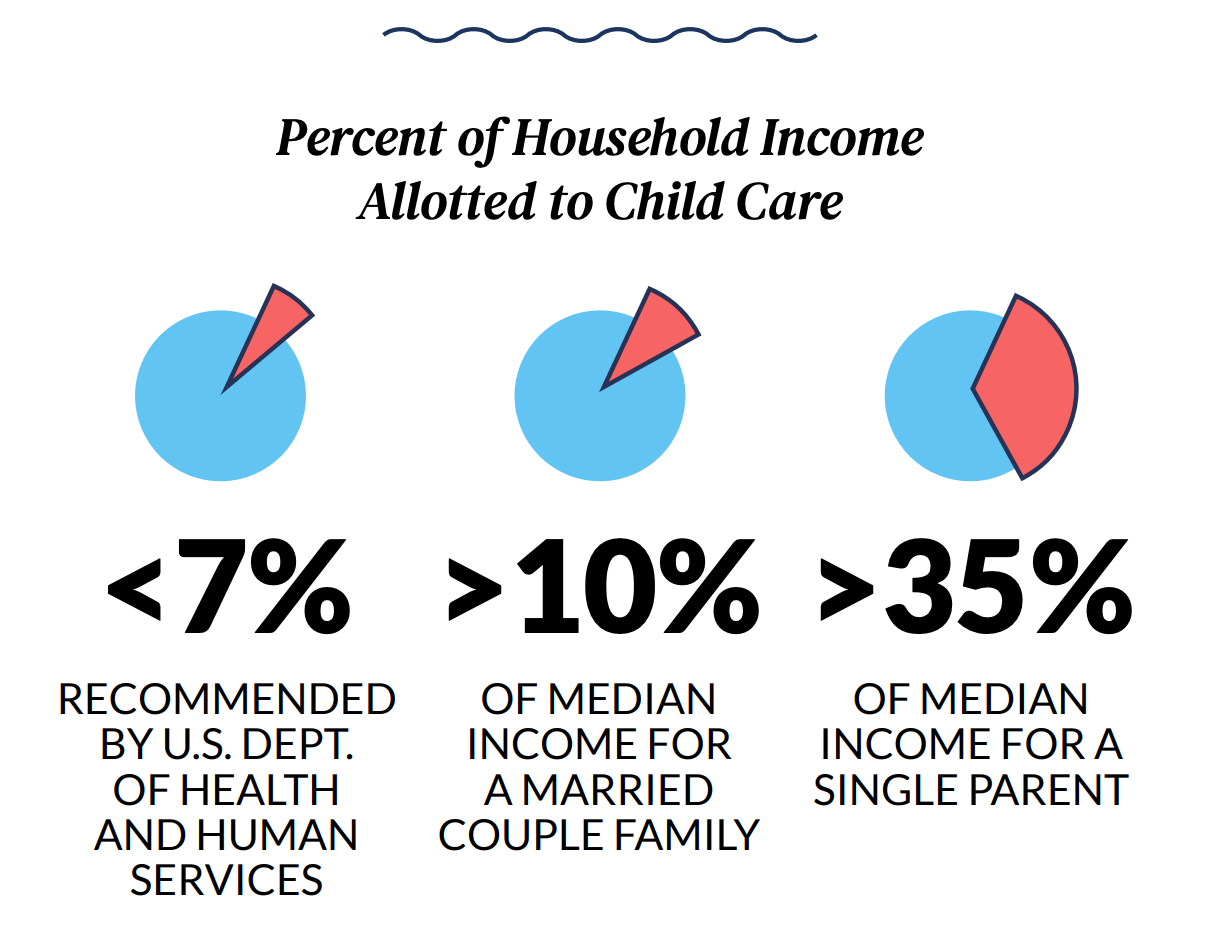

But for low-paid workers, dual income is not enough. According to a recent report from Demand Change, the national annual average cost of childcare for one child is $10,174, which comes out to $27.87 dollars a day. For the median dual-income American household, this is approximately 10% of their annual income. For a single-parent household, it’s over 35%. This is over five times higher than the Health and Human Services’ recommendation for childcare to cost no more than 7% of a family’s income. Obviously, the cost of childcare is too high, leading many Americans to make the difficult choice to leave their children home alone while they go to work. (An estimated 40% of American children are left home alone at some point in their lives.)

Publicly-funded childcare, which is typically provided through the public school system, is also sporadic and inadequate. Children begin kindergarten at age six, and from then on are supervised during daytime hours until they graduate high school at eighteen. The supervision provided by the public school system diminishes with age, as older children are more likely to be able to take care of themselves in basic tasks, such as walking to the bus stop or being home alone after school. It is not the pre-teens and teens that are in need of additional care, but young children and babies. After all, parents still need to go to work in the six years between birth and when their child is admitted to kindergarten.

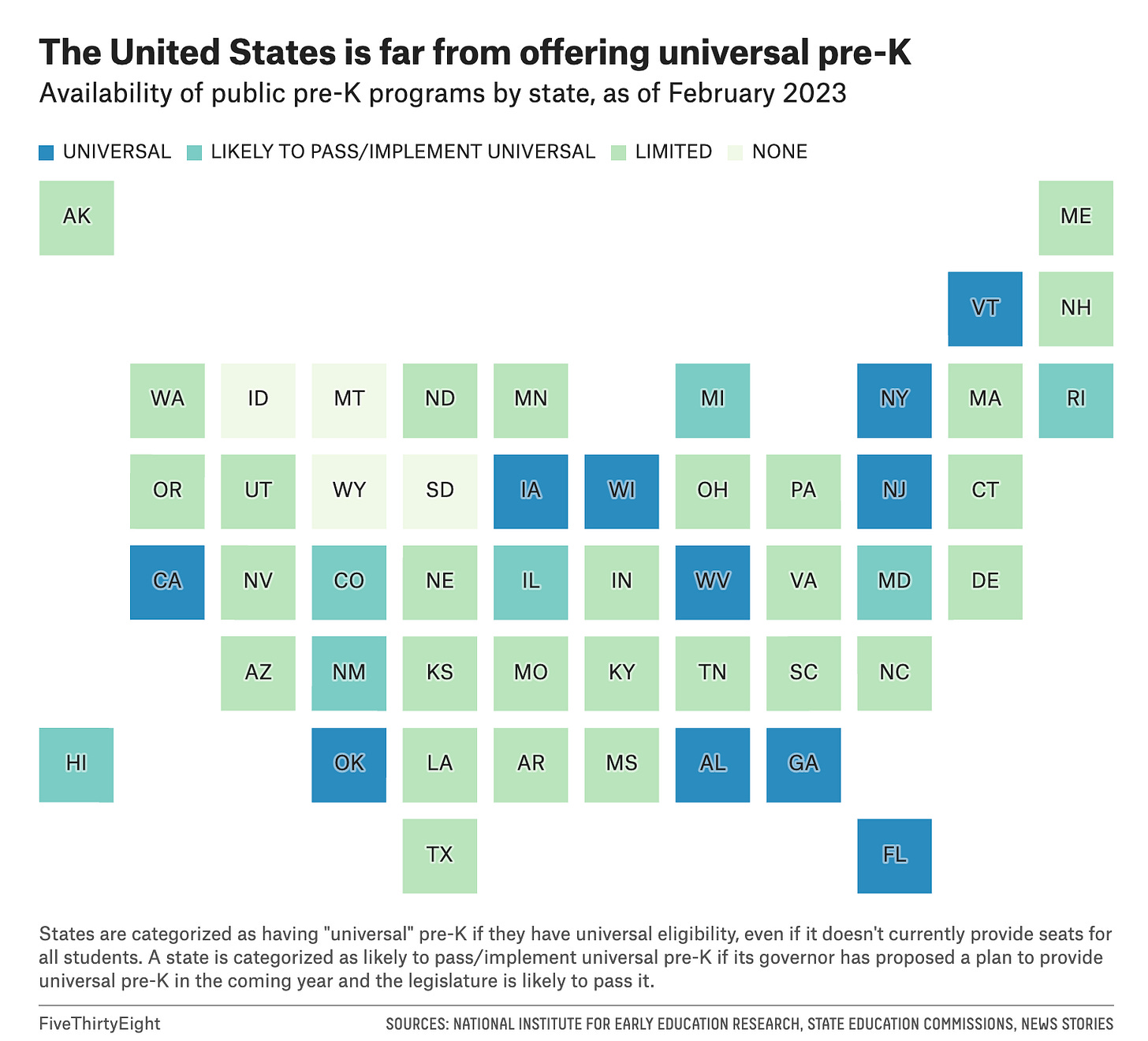

While some states fulfill the need for childcare through some form of pre-kindergarten education, the system is sporadic, variable, and in need of improvement. This chart from FiveThirtyEight shows the great variance in pre-K programs. Only Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and South Dakota have no pre-K programs, though far more states have limited programs (light green) that stretch parents’ budgets and energy.

Additionally, “pre-K” usually starts at age four, meaning parents have to find four years of expensive private care so they can go to work. There is also the issue of non-traditional work hours, which education-based childcare does not cover. Approximately 27% of American workers are on the job between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. at least once a week, meaning there is a need for robust childcare systems that go outside the traditional hours of 9 to 5.

A Solution From Our Past

To solve America’s childcare problem, we don’t need to imagine a bold new program that overhauls the entire education system. Instead, we should look to our past and reimplement what has already been proven to work.

During World War II, the United States implemented a total universal childcare program with resounding success. With every able-bodied male drafted into service, women worked in the factories, making all the guns, bombs, vehicles, and supplies the Allies needed to fight. Until the War, America had relied on women to care for their children, but with their full dedication on work, this was a job they could do no longer.