[BONUS] The History of Science Fiction

Part I - From 1616, to "Frankenstein," to "The First Men in the Moon."

Hey folks! This is the first part of a four-part series detailing the history of science fiction and how it has long been a cultural mirror for society’s dreams, fears, and ailments. Part I introduces the series and looks at the 19th-century origins of Sci-Fi and how it made its first on-screen appearances in the early 1900s. Subsequent posts will examine the Cold War era, the 80s and 90s Hollywood heyday, and finally, modern stories in movies, books, and video games.

While Part I is available to all readers, Parts II, III, and IV will be for premium readers. If you’d like to read them, upgrade your subscription for just $15 a year — that’s less than .¢15 an article.

Enjoy!

In Solidarity — Joe

Science fiction has long been one of America’s favorite genres, and for good reason. Yes, spaceships are cool, but it is the ability to replicate the struggles of the common people in extraordinary scenarios that keeps the genre fresh and exciting. Whether shown on a theatre screen or detailed in the pages of a library book, audiences gravitate to the stories that mirror their own problems, as it enables them to better relate with the protagonists and their goals while partaking in tales of great imagination.

The tendency of science fiction creators to bring real-life problems into futuristic scenarios makes the genre an excellent mirror to understand the hopes, fears, and challenges facing humanity at the time. Whether written or filmed, the majority of sci-fi takes place in a reality unrecognizable from our own, in which humanity has reached one of two outcomes: either we have conquered our flaws and reached utopia, or we have failed to move past the limitations of tribalistic nationalism and greed-driven Capitalism, for which our fate is the flash of an atomic bomb or the scream of the incoming zombie horde.

And while the genre once held a balance between dystopia and utopian stories, 21st-century sci-fi seldom takes the hopeful route. In today’s shows, movies, video games, and books, creators almost exclusively tell tales of dystopia. Whether it’s the zombie pandemic of The Last of Us or the class warfare of The Expanse, the pessimism of modern science fiction shows us that humanity is not very optimistic about our future.

Historic Origins

Since people have been telling stories, there has been science fiction. Not in the modern sense, with killer robots and time machines, but with an imagination of where the technology of the time could lead. The oldest known work of science fiction dates back to 1616. Entitled The Chemical Wedding, it tells of an alchemist invited to a mysterious castle full of inexplainable wonders and miracles, where he must aid the wedding ceremony of an extra-dimensional King and Queen.

Often considered the first “modern” work of science fiction, Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein was about much more than one mad scientist’s desire to create sentient life. Also known as The Modern Prometheus, a reference to the Greek god that bestowed humanity with the gift of fire, Shelley was inspired to write Frankenstein after a journey through continental Europe during the technological turning point of the First Industrial Revolution. Like any societal transformation, the Industrial Revolution had winners and losers. In this case, the Revolution replaced the cottage industry and left many people without a means to support themselves. Naturally, the lower classes resented the new technologies, and some, called “the Luddites” after their leader Ned Ludd, tried to destroy textile machines with fire and axe. Traveling through the towns and cities undergoing this change, and likely conversing with those in the lower class who were harmed by the Revolution’s progress, Shelley wove a tale articulating both the positive and destructive results scientific development could bring. Throughout her novel, the townsfolk are always present, a distinctive departure from other works that typically focused on royalty and the elite.

As the 19th century continued, the unsettling of the First Industrial Revolution subsided and people began to appreciate the technologies it had produced. Though there was great hardship in their journey, millions of immigrants boarded steamships to cross the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in hopes of a better life in the United States. Once there, they settled in the industrial hubs of New York, Boston, and Chicago. Or, if city life was not for them, they ventured West to search for gold or partake in the building of American railroads. Though the lives of immigrants, newly freed slaves, and wage laborers were filled with oppression and hardship, there was an air of adventure in the latter half of the 1800s. The slavery issue, which had divided America for generations, had been “solved,” freeing the literate to spend less of their time on politics and more pondering how new technologies would facilitate great adventures.

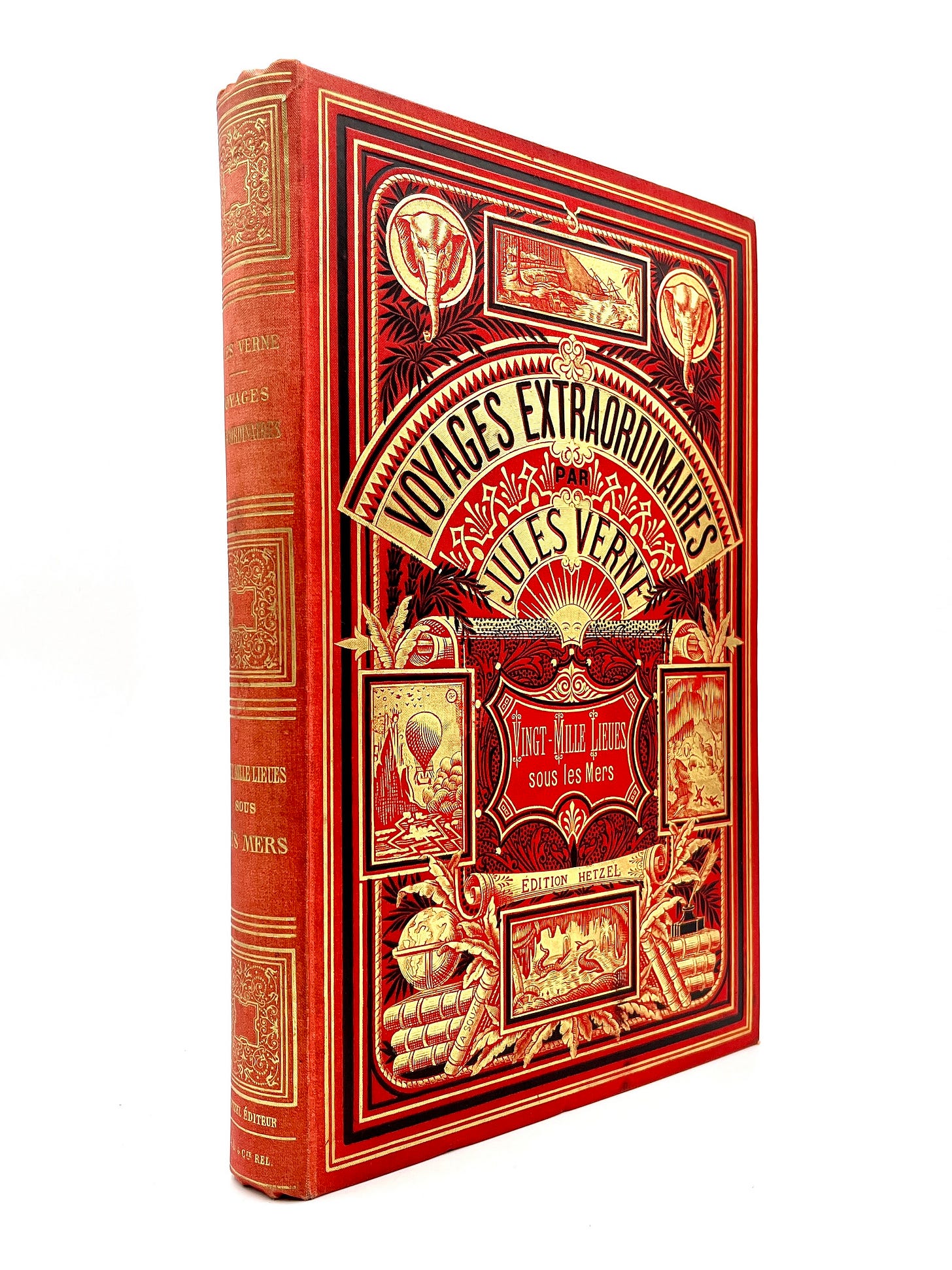

It was at this time the great Jules Verne wrote his three-part collection of “The Voyages Extraordinaire,” two of which became science fiction classics. Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) details a (you guessed it) journey to the center of the Earth, where the protagonists find a prehistoric world perfectly preserved. Six years later Verne published Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas (1870), which featured the highly advanced submarine, Nautilus. At the time, submarines were clunky, unpractical vessels, but Verne, borrowing from the advancements in seafaring and transportation happening all around him, was able to foresee many of the sub-aquatic technologies that were soon to come.

The 20th-Century Looks Up

By the turn of the 20th century, the American continent had been fully conquered, leaving the Earth fully mapped. With the planet explored, curious minds began to look upward. Though they were far from the first to try, the Wright Brothers cemented themselves in history by being the first to achieve sustained, horizontal flight, an achievement that was the culmination of decades of attempts made by numerous scientists the world over. And with all their attention on the sky, it was only a matter of time before humans were drawn to the bright, shining satellite hanging over their heads.

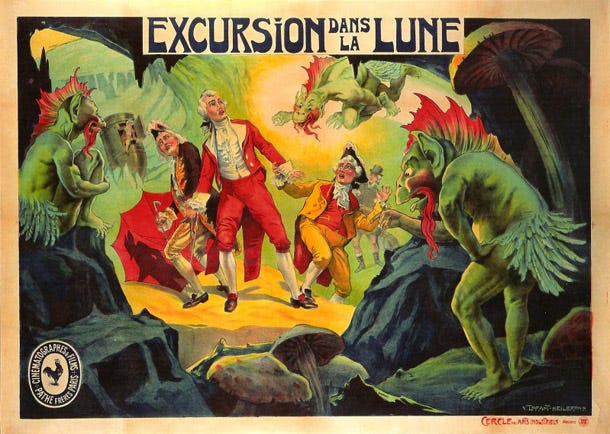

H.G. Wells’s 1901 novel The First Men in the Moon went where aviators could not, depicting a journey to the moon via a machine made of anti-gravity material. Once the protagonists arrive upon the celestial body, they battle the insectoid “Selenites” who live in the subterranean (or, whatever the word for “sub-moon surface” is) levels. The Selenites would return in their first on-screen appearance in the 1903 French film, A Trip to the Moon, a composite work of many moon-faring novels and stories, of which H.G. Wells’s novel was one. What the heavens held was the subject of great fascination, and would go on to define the first decades of 20th century science fiction, most famously with the works of Spanish silent-film director Segundo De Chomón, who offered his own creative take with the 1908 film Excursion to the Moon and ventured deeper into the solar system with the 1909 picture A Trip to Jupiter.

But as the world turned its attention from the wonders of space to the devastation of two world wars, science fiction went with it, taking on a much grimmer and pessimistic view of humanity. Part II will look at science fiction during the post-war period, exploring the cult classics of Alien, Mad Max, and of course, Star Wars.

Subscribe so you don’t miss it.

What do you think about the early history of sci-fi? Are there any classic works I missed that you think are important to discuss? Share your thoughts in the comments.

Joe, I don't know if this had anything to do with "Sci-Friday", but this is very timely. Something like 10 folks wrote about their favorite sci-fi stuff today; your piece is good and really adds a lot to the conversation! I also like going way back when thinking about sci-fi, especially to The Verae Historiae - but I wonder if we might argue for an even earlier beginning. Nothing is documented from ancient Greece, but they sure had some advanced technologies back in the day, including primitive automata and a design for a working steam engine, etc.

Great start, very curious to see what you include as the piece progresses.