How American Shock Capitalism Fostered the Russia-Ukraine War

America gave Russia capitalism. Russians didn’t like it, so Putin gave them nationalism.

Director Quentin Tarantino coined the term “Marvelization” to describe how Marvel movies made audiences hyper-loyal to the main character. According to Tarantino, instead of recognizing Chris Evans as the star of Captain America, viewers idolized Captain America himself. Whatever the superhero did was inherently good, and whoever opposed him was evil. No questions asked.

As the Marvel tidal wave has overtaken American society, Marvelization has expanded beyond the cinema into far-reaching facets of life, most notably geopolitics. Instead of trying to learn the causes of war, which would help us prevent further outbreaks of violence, conflicts are oversimplified as “Good Guys vs. Bad Guys.” Through this frame, the Ukraine-Russia War has been reimagined as a cinematic battle between Thanos and the Avengers.

Viewing the world as good vs. evil isn’t new, but it is used to describe the Ukraine-Russia War with a fervor not seen since 9/11. As many Americans are naive to the relationship between the former Soviet states, this easy-to-understand dichotomy simplifies an otherwise complex issue. While few dispute the lion’s share of the blame lies with Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine, discussing the war as “good guys vs. bad guys” doesn’t tell us how the “bad guys” came to power or why they made their choices. This ignorance leaves our response wanting and makes the world vulnerable to similar conflicts. If we want to end the Russia-Ukraine War and prevent future tragedies from occurring, we must discard Marvel-esque framing to truly understand geopolitical actors, the conditions they exist in, and the reason they embark on the warpath.

Unfortunately, as the Russia-Ukraine War crosses its two-year mark, there’s been little inspection by American corporate media into the underlying issues that brought Europe to war. The lack of coverage isn’t surprising, given the causes of the war are nuanced, dated, and lay some of the blame at the feet of American capitalism.

Shock Capitalism

To understand the Russia-Ukraine War, we have to understand contemporary Russia, which rose from the ruins of the Soviet Union.

On Christmas Day, 1991, Michael Gorbachev resigned as President of the Soviet Union, formerly ending the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.). Boris Yeltsin became President of the newly independent Russia and immediately began deconstructing the Soviet planned economy in favor of a market-based capitalist economy. Everything from hospitals, to construction firms, to the oil industry was sold to wealthy investors.

Yeltsin wasn’t flying by the seat of his pants. He was following Milton Friedman’s doctrine of Shock Capitalism (a.k.a. “Shock Therapy”), a blueprint to rapidly transition a socially owned economy into a privately owned one. The process had previously been used by Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet who sought the U.S.’s help in erasing the socialist programs of his predecessor, whom Pinochet had overthrown in a CIA-backed coup.

As with Pinochet’s Chile, Russian Shock Capitalism was a disaster. The overnight removal of socialist industry and collective programs led to what British journalist Seumas Milne called “the most cataclysmic peacetime economic collapse of an industrial country in history.” The facts support Milne’s claim. In less than a decade, Shock Capitalism decreased Russian national income and real wages by 50%, while life expectancy fell by 10% in less than three years. In the long run, income inequality has skyrocketed. As of 2020, the wealthiest 1% of Russians held over half the national wealth, almost double the amount held by the top 1% of Americans.

There’s little debate about the cause of Russia’s economic woes. Regardless of what one thinks about a Soviet-style centralized economy, selling it piece by piece meant it was bought by the only ones who could afford it: wealthy, well-connected criminals. When the Russian government sold former Soviet assets, they often did so for pennies on the dollar to their friends, creating the network of Russian Oligarchs that still exist today.

During the Shock Capitalism process, neoliberals, especially Bill Clinton, insisted Russia’s “democratic gains” would outweigh the heavy social costs. As many predicted at the time, this argument failed to materialize. Since being hand-picked as Yeltsin’s successor, President Vladimir Putin has tightened domestic control and reinforced the oligarchy. Naturally, the Russian people aren’t thrilled with hyper-capitalist economics and limited civil liberties. Faced with an increasingly growing opposition, Vladimir Putin did what many of history’s unpopular leaders have done. He went to war.

Nationalism Leads To War

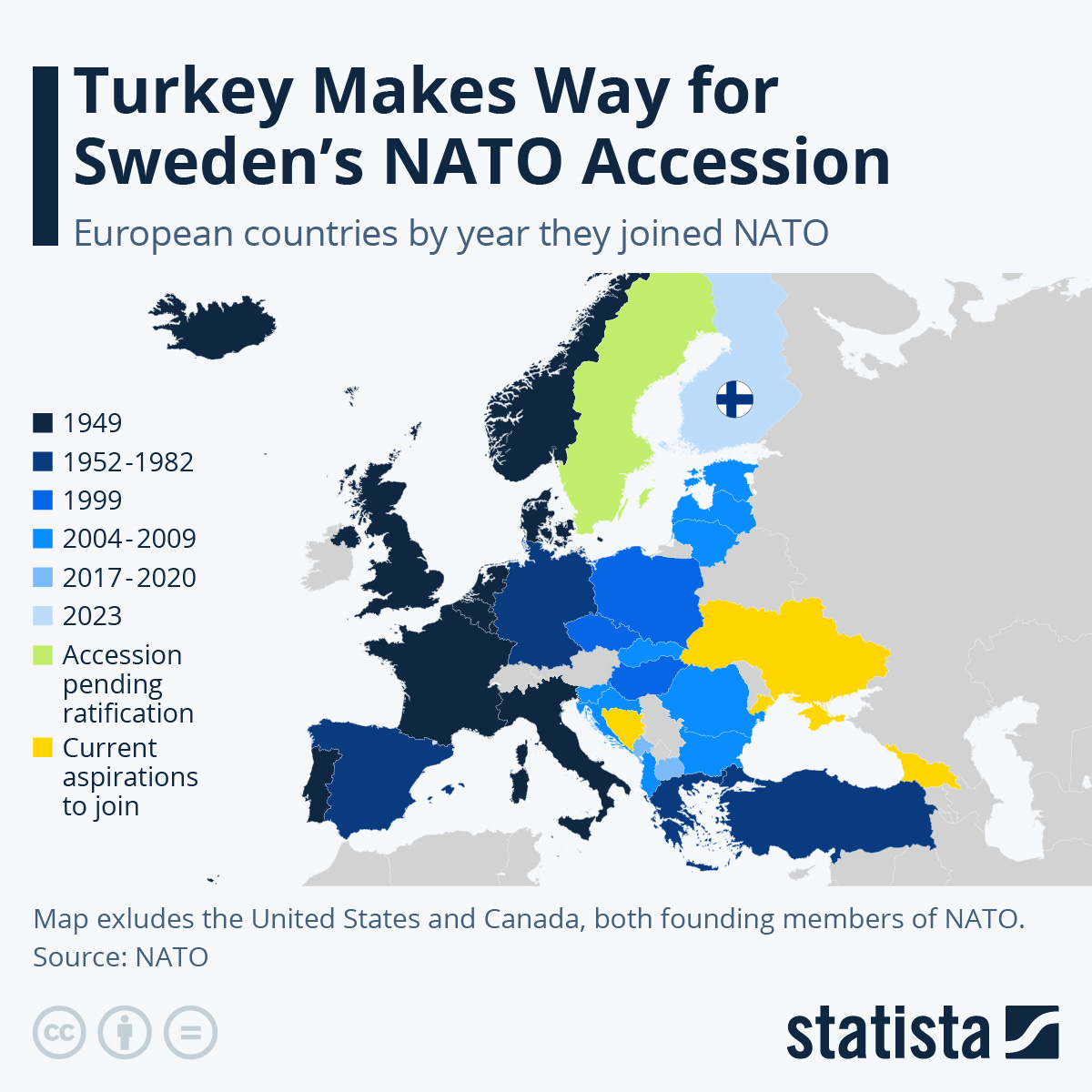

Since Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine forty-eight months ago, pundits, politicians, and the public have speculated on Putin’s motivation. One of the most common explanations is the expansion of NATO. The below chart shows how, despite U.S. assurances that NATO would not move “one inch east” after the end of the Cold War, the alliance has gradually added members and crept toward Russian borders.

Before 2022, everyone from Henry Kissinger to Jeremy Corbyn warned increasing NATO could threaten Russia and provoke a war. NATO encroachment does not excuse Putin’s decision to invade, but one doesn’t need to sympathize with a tiger to know cornering it will cause bloodshed. While Putin lists NATO expansion as one of his motivations, as he has repeatedly stated, there were more prominent concerns.

In their recent interview, Tucker Carlson opened with a leading question asking Putin why he invaded Ukraine. While Carlson clearly wanted Putin to point the finger at NATO, the Russian President went in a different direction. For the first 20 or so minutes of the conversation, Putin detailed Russian history going back to 882, arguing that Ukraine was part of Russia and had wrongly by granted independence by Stalin and Lenin. This is consistent with the national address he made on the eve of the invasion.

“I would like to emphasize again that Ukraine is not just a neighboring country. It is an inalienable part of our (Russian) history, culture and spiritual space… Modern Ukraine was entirely created by [the] Bolsheviks. Lenin and his associates did it in a way that was extremely harsh on Russia; by separating what is historically Russian land. — Putin’s Pre-Invasion National Address, February 21st, 2022

This is a nationalist argument. While he has addressed the fear of NATO encroachment, Purin has reiterated his paramount motivation is to reclaim what he believes is historic Russian territory. I do not doubt Vladimir Putin believes Ukraine should be a part of Russia. But, we should not assume that belief is shared throughout Russia. Instead, we should recognize that, much like American, British, or any other form of nationalism, Russian nationalism is a useful tool to distract the impoverished masses from their misery. As explained above, life for the median Russian in 2024 is bleak. Their income is low, their lives are short, and the oligarch class is consuming more of their national wealth than ever before. Naturally, unrest and protest are common. The rolling protests of 2011 to 2013 that began in opposition to Putin’s return to the presidency are estimated to be the largest modern Russia has ever seen. With the 2024 election likely to climax public unrest, a shot of militant Russian nationalism was just what Putin needed to direct Russian frustration outwards.

By invading Ukraine, Putin gave the Russian people something else to think about. Much like American discontent was historically directed towards the frontier, and then to foreign adventures after the continent was settled, Vladimir Putin’s decision to bring Russia into direct conflict with Europe and America focused his nation’s dissatisfaction outside Russia’s borders. By all available metrics, this tactic worked well. The below graph shows Putin’s approval rating over time. Since 2000, he’s enjoyed steady approval ratings with two noticeable jumps: The 2014 invasion of Crimea (65% to 85%) and the 2022 full-fledged invasion (69% to 83%). You’ll notice both of these acts came after sustained decreases in Putin’s popularity.

Some will doubt the accuracy of Putin’s approval ratings, but regardless of whether his true favorability is accurate, the spikes indicate modern Russia is no different from past and present nations: rulers can increase their popularity, quell dissent, and consolidate power via war. Of course, this analysis is incomplete without recognizing why Putin felt the need to strengthen his position in the first place. While the late Soviet economic policy was far from perfect, the data shows it was significantly better than the authoritarian oligarchy currently in place. With no collectivist economic belief and no fair share of the capitalist wealth, the Russian people, like their global brethren, became dissatisfied. Autocratic societies can’t entertain even minimal dissent, as the people know they have no method of electoral change and are quicker to more drastic action. (This is especially true in Russia.) War, as it has long done, quieted the discontent via a campaign of public nationalism and state repression, not unlike the post-9/11 blueprint implemented by the Bush Administration.

As the Russia-Ukraine War passes its second birthday, it’s increasingly appearing like it will remain a brutal stalemate. While there’s no easy answer to end the bloodshed, what I can confidently state is that American Shock Capitalism (and to a lesser degree, the expansion of NATO) fostered the conditions that birthed this devastating conflict. We can’t change the past, but we must learn from it. If we truly want to prevent future wars like this from occurring, the United States should remember how we helped the oligarchs steal Russia from its people.

Thanks for reading. If you appreciate this post, don’t forget to subscribe (and like this article) so future dispatches are delivered straight to your inbox.

Milton Friedman holds an eternal high-ranking slot on my Shit List.

Thanks for putting this together, a really helpful re-contextualization after a few months of not thinking about this.

Excellent analysis.