The Big Three Automakers Could Accept Every UAW Demand And Still Be Extremely Profitable

I hope you like charts and arithmetic.

Welcome to JoeWrote, a publication where I explain the reasoning behind progressive and socialist politics. Today’s piece is looking at the math behind the United Auto Workers’ contract demands. Ensure you don’t miss future articles by becoming a free or premium subscriber.

You can also help JoeWrote grow by liking (click the ❤️ button at the top) and forwarding this post to a friend. Thank you for your support.

In Solidarity — Joe

It’s officially fall, but don’t worry — Hot Labor Summer isn’t over yet.

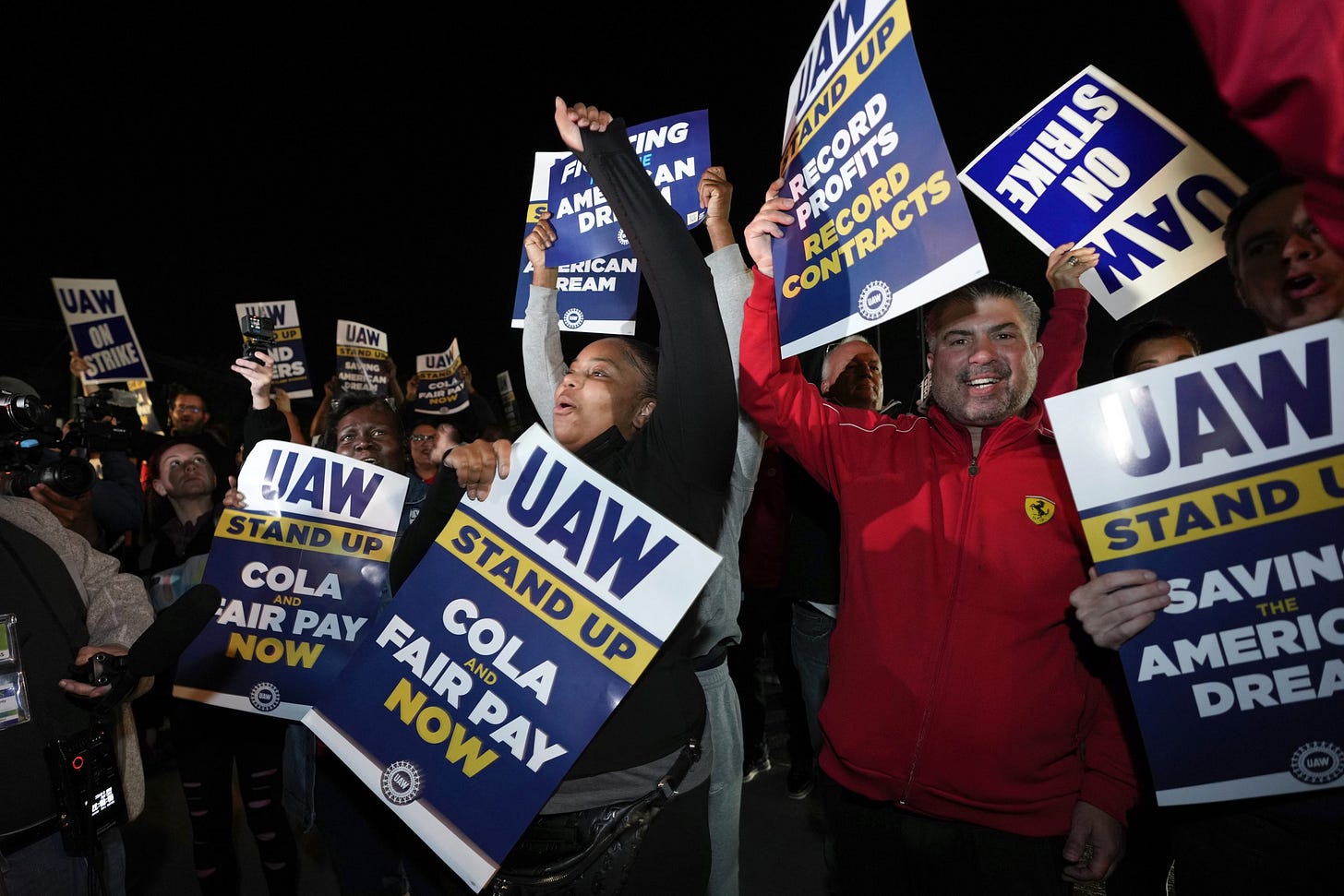

Two weeks ago, the United Auto Workers (UAW) announced a strike against the “Big Three” automakers of Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis (the parent company of Chrysler). It’s the first time in history the UAW has struck the Big Three simultaneously.

The UAW is using a rolling strike strategy, which, instead of striking everywhere at once, calls plants to halt work one by one. On Friday, UAW President Shawn Fain asked 7,000 more workers to walk off GM and Ford plants, a sign that at least two of the three companies were refusing the union’s demands.

The strike has gotten a lot of media attention, and while some of it has been good, I have yet to see an outlet clearly report that the Big Three could give everything the UAW is asking for and still remain a profitable company.

What the UAW Demands

The workers’ demands are quite clear. They are striking for:

36% pay increase over four years,

A 32-hour (4-day) workweek,

Reinstatement of cost of living adjustments (COLA), which match their wages to inflation,

Pensions for every employee,

An end to the two-tiered wage system.

While the auto executives are trying to make these requests sound unreasonable and sure to “hurt the economy,” the numbers show that the Big Three companies could afford everything the workers have asked for.

Between 2013 and 2022, profits for the Big Three rose by 92%, totaling $250 billion dollars. Even with the strike, they’re forecast to rake in $32 billion this year. Executive pay at these companies has risen 40% during the same period, all while workers have seen their real hourly wages fall by 19.3%.

Not So Fun Fact: In 2022, Ford CEO James Farley made $21 million, Stellanis CEO Carlos Tavares made $24.8 million, and GM CEO Mary Barra made $29 million (#girlboss). These salaries are 281 times, 365 times, and 362 times what their median company worker made, respectively.

There are about 150,000 UAW workers employed by the Big Three. That means each UAW worker created $1.66 million in profit over this time, despite their real wages falling. (250,000,000,000 / 150,000 = 1,666,666)

In order for the claim that the UAW demands “threaten the economy” to be true, the cost of the demand would have to be more than the combined company profits and extravagant salaries of the Big Three executives.

Wage Increase & Shorter Workweeks

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average hourly earnings of an auto worker is $27.99, or about $55,980 annually, on the standard work week (40 hours a week, two weeks off for vacation). A 36% pay over four years would raise this to $38.07 an hour, or $76,132.80 annually

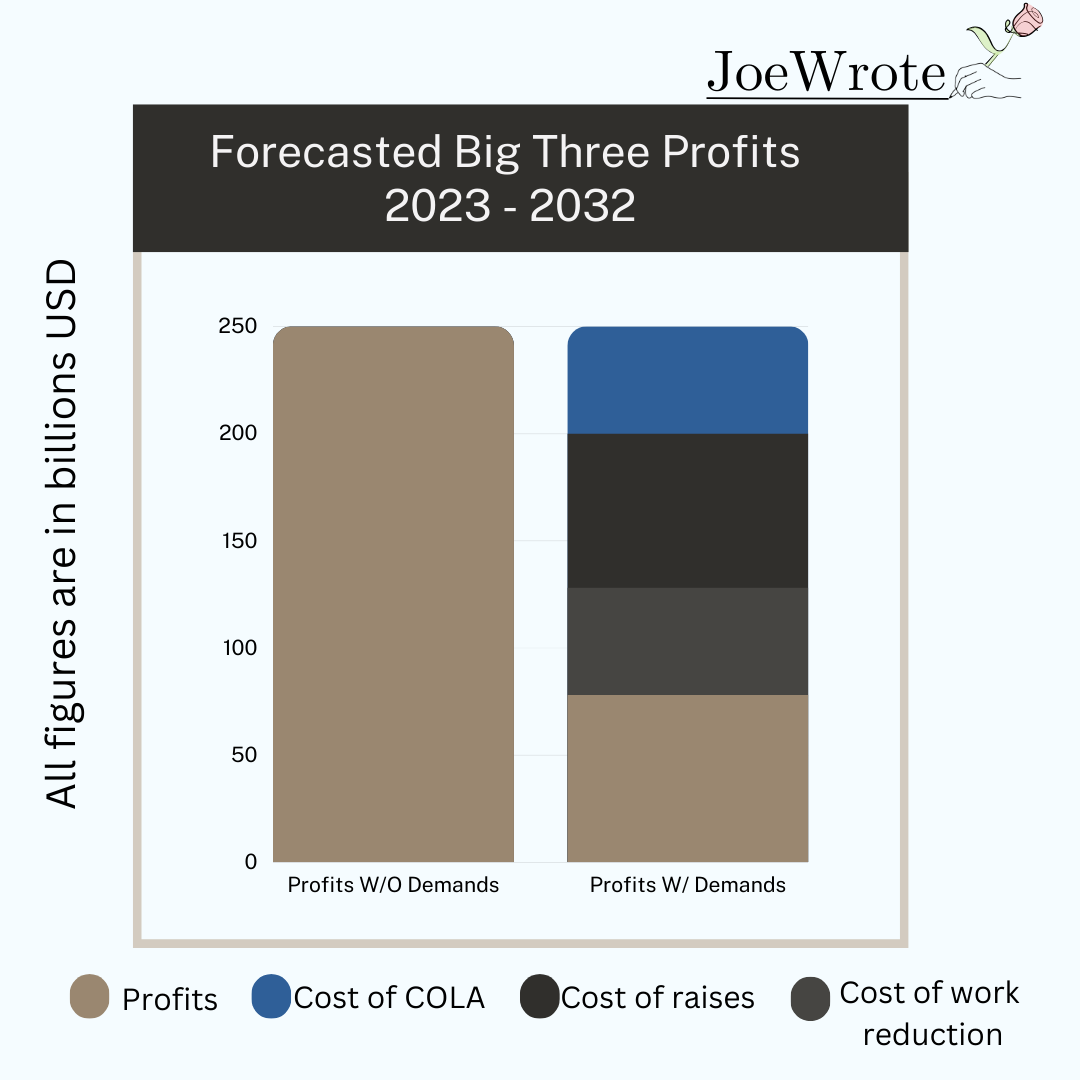

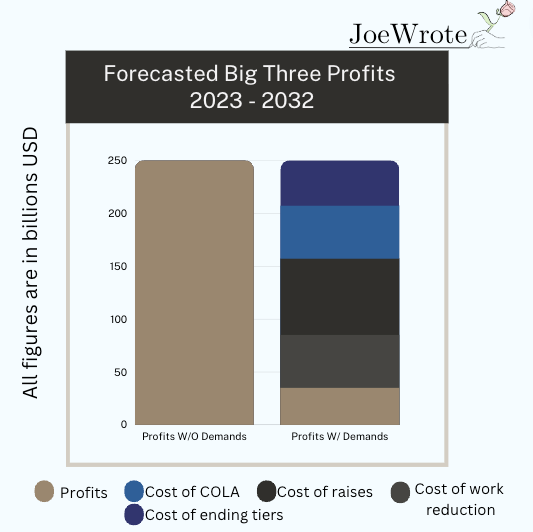

But workers are also asking for this pay raise while working hours are reduced to 32 hours a week. Remember, the Big Three made $250 billion in profits over the last ten years. I’m going to be generous to them and assume this is what they’ll make over the next ten years, though given they have increased profits every year since 2020, all signs are pointing to them making more than $250 billion over this timeframe.

But for simplicity, we’ll assume they’ll make this $250 billion again between 2023 and 2032.

Let’s assume a 20% decrease in working hours (40-hour work week to a 32-hour work week) would cost companies 20% of their profit. That means they would make only $200 billion in profit over the next decades. Factor in the 36% raise in wages would cost them 36% in profit ($72B), netting them approximately $128 billion over the next decade.

COLA

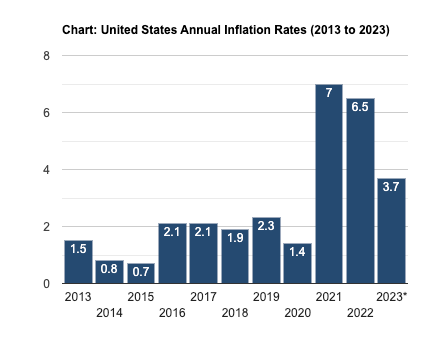

A key sticking point in the negotiation is the reinstatement of cost of living adjustments (COLA) which balances wages against inflation. COLA clauses were once commonplace in union contracts. 61% of unionized workers had one in 1976, compared to only 22% in 1995, the year the BLS stopped tracking the data. UAW workers gave up COLA provisions in their 2009 contract, with the promise they would be reinstated once the companies recovered from the Great Recession. And yet, to our great surprise, the Big Three went back on their word and did not reinstate COLA, letting workers’ real wages fall as inflation skyrocketed.

There’s no definitive way to calculate what COLA will cost the Big Three, as we can’t predict inflation. (This is actually why COLA exists, but I digress.) But we can estimate. Over the last ten years, inflation rose by a median rate of 2% every year. Were a standard COLA implemented, that would equate to a 2% raise in worker wages every year, an approximate 20% decrease ($50 billion) in the Big Three’s next decade of profits. That brings their forecasted profits to $78 billion over the next decade.

Ending Tiers

If you’ve been paying attention to the strike, you’ve likely heard of the tier system, which results in workers who do the same job being paid different wages. It’s important to note that tiers aren’t pay bands or reflective of well-earned raises. They are based on when the worker was hired, as the Big Three pay less wages to those who became employed under more recent contracts.

Under the tier system, workers hired after 2007 are paid less and get 401(k)s instead of pensions. As I’ve written previously (below), 401(k)s are inadequate to support a worker through retirement, as they are just a way to defer wages, as opposed to pensions which are paid for by employers. As the upper-tier workers, who cost the company more, retire, only second-tier workers will remain, who will eventually make up the entire workforce. The tier system becomes even more byzantine, as it is currently being used to hire electric vehicle workers at below-industry wages.

401(k)s Are Failing Americans.

Welcome to JoeWrote. You can support my work by liking this article (click the ❤️ button at the top), forwarding it to a friend, or subscribing to become a free or full reader. Annual plans cost just $15 a year. Thank you for your support. In Solidarity, Joe

Given the nature of the tier system, where a worker’s wage and benefits can vary greatly depending on the location of the plant, the type of work they do, and whether or not they are considered “temporary” (that’s a misleading term, as some GM workers are “temporary” even after four years of employment), there’s variance in how much ending the tiers will cost the Big Three.

On average, a first-tier employee earns $28 an hour while a second tier earns between $16 and $19, or approximately $35,000 annually. 70% of UAW workers (105,000) are second tier, which currently costs the Big Three $37 billion for ten years of their labor. Were these 105,000 workers to be lifted from second-tier status and receive the $76,132.80 annual pay that would come from a first-tier salary raised by the 36% wage increase demand, that would increase their labor costs from $37B to $80B, a net change of $43B. Were this to be enacted, Big Three profits over the next decade would remain at $35 billion over the next decade.

Pensions

The true cost of pensions is difficult to calculate, as it depends on the lifespan of retired workers, and when they choose to retire. But we can get an estimate.

According to the Wayne State University’s School of Business, pensions for first-tier retired UAW workers cost the company about $18,000 a year per retiree. If we assume workers retire at 65 and live until the life expectance of 77, that means they would each collect $216,000 from their employers after retirement (12 years x $18,000 a year). We also know that approximately 16.8% of Americans are retired. Using this, we can estimate that each year, the Big Three will pay a pension of $18,000 to 25,200 workers (16.8% x 150,000 UAW workers). That’s $453,600,000 a year which equates to approximately $4.536 billion over 10 years. Were a pension extended to its entire workforce, the Big Three would still rack in approximately $30.464 billion over the next ten years.

So there we have. Chrysler, GM, and Ford could give the United Auto Workers everything they are asking for and still reap over $30 billion in profit over the next decade. Even if the estimates we’re forced to work with are somewhat off, $30 billion is a lot of money, more than enough to cover any of the miscellaneous expenses that won’t be known until the ink has dried on the new contract.

Inevitably, there will be some who will see this data and claim, “If the Big Three go from making $250 billion to $30 billion, that will be bad for the economy, as investors are less likely to invest!”

To that, I agree. Investors will probably be less likely to invest, but that is not “bad for the economy” nor the fault of the workers. The potential hesitation of investment firms is the fault of capitalism. Through this exercise, we have seen the Big Three’s gargantuan profits have come at the expense of workers. Now, the workers are fighting back and demanding more of the value they create. That inherently threatens the capitalist system, as capital will naturally invest in where workers are most-exploitable. In arguing that the UAW demands are “bad” for the economy, anti-union advocates are admitting that the current socioeconomic system is one built on exploitation of workers.

While we should stand with auto workers and help them get the deal possible, let us not forget that the final goal is not to simply reduce the exploitation of the worker, but end it.

Hey folks! Joe here. I hoped you liked this explainer of the UAW contract negotiations. If you did, I’ll ask you to please consider becoming a premium subscriber. I’m not usually this forward about asking for subscriptions, but this article took a lot of time to research and write. If you enjoyed it, please consider supporting my work for just $15 a year. As a thank you, you’ll get an extra article every week, in addition to other bonus content.

Thanks again! Joe

I’m 100% with you and the workers on everything but a pension. Unless the UAW’s plan has a killer multiplier, fighting for a huge fixed contribution first (and match second) is the way to go.

I’m especially hopefully they get their ask for a shorter work week. IMO, that could set a massive precedent across the manufacturing and transportation sectors.

Wow, I love it when people actually do the math! (not my strength). Since we live in upside down world, I vote we invert the top-tier wage triangle, and let the CEOs live off the wages and 401k (with generous performance review bonuses, and split all the profits among the workers. Haha.