The Case for Economic Democracy: Chapter 7.1

The "S" Word

Welcome to Chapter 7 of my book, “The Case for Economic Democracy.” It’s released chapter-by-chapter to premium subscribers, every Friday. If you’d like to read it — as well as support my work and access every JoeWrote has to offer — upgrade to a premium subscription today.

Thank you for your support, and enjoy your weekend! - Joe

Welcome to Chapter 7 of The Case for Economic Democracy! As you may have noticed, the passages of this book have yet to use the terms “Socialism” or “Capitalism.” This was a purposeful choice, as I want readers of this book to weigh the argument of economic democracy on its merits without the emotion caused by these political terms. But as the book ends, it is important to bring in these terms to make the clarifying point — Socialism is economic democracy. Capitalism is economic tyranny.

Chapter Seven: The "S" Word

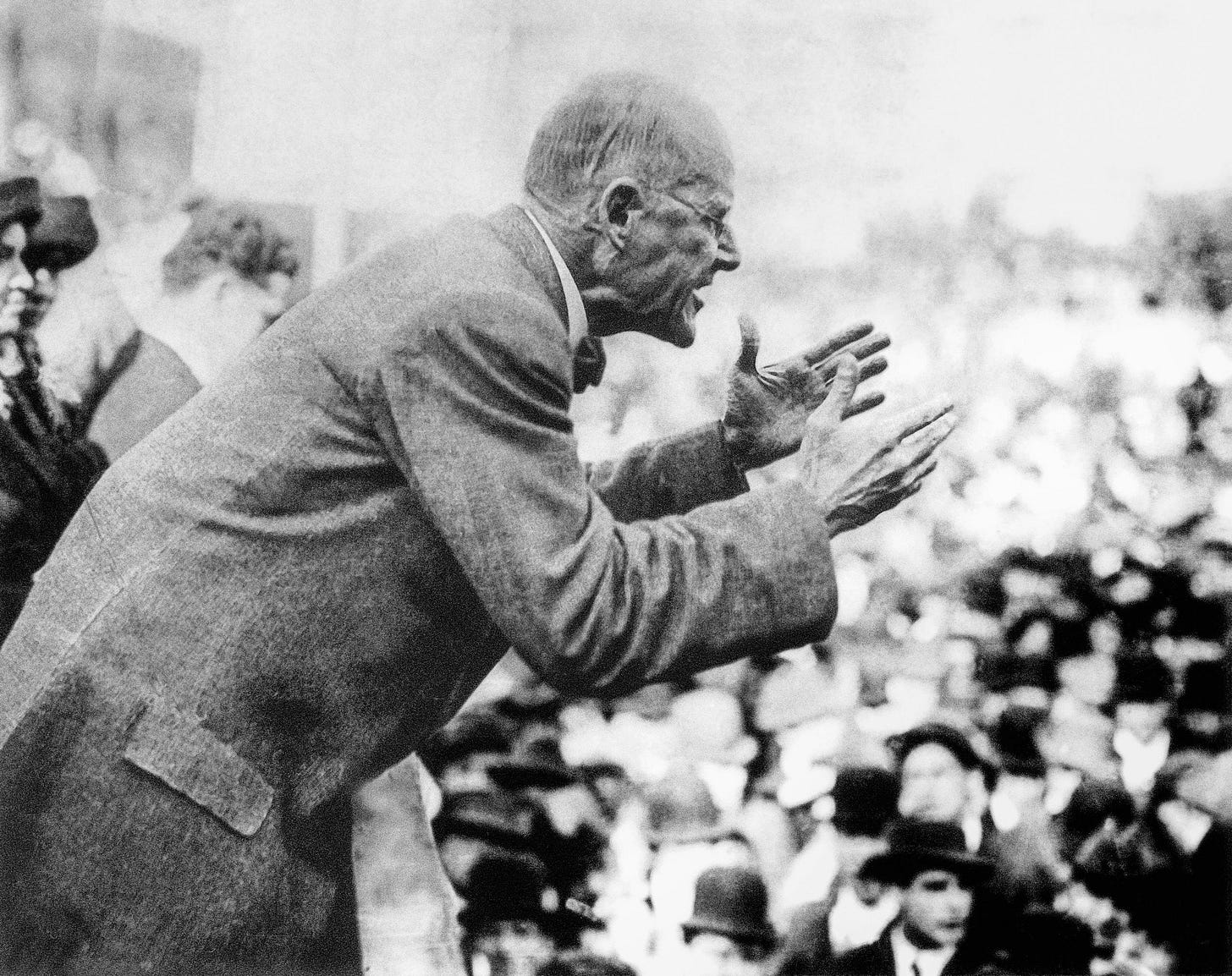

“Socialism is merely an extension of democracy into the economic field.” - Eugene V. Debs, 1908.

For a book focused on the economy of modern America, it may seem odd that the terms “Capitalism” and “Socialism” have been entirely absent. Their omission is by design. These terms are so politically loaded, that merely muttering them causes some audience members to recoil and withdraw to their ideological corner, raising shields to defend their preferred “team” instead of regarding the two systems on merit. I purposely chose to not use the words “Capitalism” and “Socialism” until this conclusion, as I wanted you to get a firm understanding of the realities of each, without being bogged down by preconceived notions.

Now that we’ve established an understanding of how American business influences your life, and the need for economic (as well as further political) democracy, we can bring the always-contentious “Capitalism” and “Socialism” into the discussion to properly describe what the previous pages of this book have discussed.

Explaining Capitalism

With few exceptions, the entire world is Capitalist. Most businesses are privately owned, and workers are hired to produce products in exchange for a wage. A handful of countries have adopted Socialist characteristics, but as they still operate within the global neoliberal system, they are no more than sporadic islands in the vast, Capitalist ocean.

It is important to be clear about what “Capitalism” means. Capitalism is the private ownership of the means of production. This is a fancy way of saying it is an economic and social system in which capital — the things that make things — such as factories, stores, tools, computers, software, and other production instruments are privately owned by individuals. As previously covered, these businesses may be owned by a single person, thousands of stockholders, or any number of owners in between. Whatever their makeup, these owners are the ones who determine the company’s operation, usually through board members. And as the owner of the businesses and industry, they are legally entitled to collect their company’s profits, sometimes called “dividends.”

Under Capitalism, the workers, who build the products or fulfill the services that make a company valuable, have no decision-making power. And because the owners are always taking profit, nor do workers collect the full value of the goods and services they produce. Instead, they are paid a wage, comprised of money, perks, and benefits. With no control over their workplace, workers under Capitalism are subject to economic dictatorship. And whenever that dictator decides they no longer want or need the worker, they are fired, depriving them of their ability to purchase shelter, food, and happiness.

Contrary to popular belief, Capitalism is not synonymous with “markets.” Cold War propaganda (from both the United States and the Soviet Union) has misled the world into thinking Capitalism is the voluntary exchange of goods and services for currency, while Socialism is when a strong central government plans and produces goods based on what they think humans deserve, want, and need. This understanding is false. In fact, both Capitalism and Socialism utilize a combination of markets and central planning.

As previously discussed, most American homes receive electricity through power lines. (If you look out your window, you can probably see them.) They also pay an electric bill to a Capitalist company. Yet, there is no market for electricity. The homeowners and renters did not research the prices and performance of various electric companies to decide which one best suited their needs. Rather, the American electrical grid is centrally planned by state and federal governments, which work hand-in-glove with Capitalist companies to ensure every American has power. These companies are required by law to deliver electricity to every home in their jurisdiction, even if it would not yield them a profit. This is central planning in action. The government decided where and how to distribute a good (electricity) to consumers (American homes). Yet, the power grid is also Capitalist, as it is privately owned and seeks a profit. Therefore, it is fair to say America’s electric grid, like many other industries, is both Capitalist and centrally planned.

Markets and central planning are merely methods of distribution. They are ways to get goods and services to people. But the method of distribution is not what makes something “Capitalist” or “Socialist.” That is determined by who controls and profits from the production of goods.

Explaining Socialism

Opposite Capitalism on the economic democracy spectrum is Socialism. The term “Socialism” carries a lot of preconceived baggage, hence why we have yet to use it. Denigrated by both the Democrat and Republican Party, “Socialism” has largely been misunderstood to mean:

· Big, authoritarian governments,

· Restricted civil liberties,

· High taxes,

· Uninspiring architecture,

· Bureaucracy,

· Central planning, and

· Anything and everything that is “bad” or “un-American.”

But Socialism is none of these things. It is simply, economic democracy.

As Capitalism is the private ownership of the means of production, Socialism is the collective ownership of the means of production. That means that if an individual is impacted by the operations of a business or industry, they should have a say in how it is run. A good reference to think about this is similar to the structure of American Federalism. As residents of Nevada and Vermont are equally impacted by the actions of the President of the United States, people in both states get to vote for who should hold the office. But as Nevadans are not impacted by the policies of the Vermont Governor, they do not get to vote for that office, and vice versa. Socialism applies this same philosophy to industry.

As someone who lives in Vermont is not impacted by the operations of a factory in Nevada, the Vermonter would not have a say in how that business operates. Those decisions would be left to those impacted by the Nevada factory, such as the workers and the nearby residents who live underneath the factory’s chemical outputs. In such a scenario, turning the Nevada factory into a worker cooperative well-regulated by a state government would give everyone impacted by the factory’s operations a democratic say, while excluding those who have no stake in the matter. But were that factory to expand its scope to the point its outputs affected the residents of Vermont, say by producing toxic chemicals that harmed the East Coast air quality, then it would be necessary for Vermonters to have a democratic say in the operation. This could be materialized through strong regulation from the Federal government or the nationalization of the factory. This practice, the democratization of economic institutions, is the beating heart of Socialism. From it, and the primary challenge of eliminating the division of the classes between workers and owners, Socialists find answers to all manners of political questions.

Inspection of the policies and platforms of international Socialist organizations and parties will show they hold concerns that seem distant from questions of the economy. But no matter how detached from the cause of economics these auxiliary goals may seem, they are an outgrowth of the belief that all humans are equal and deserving of democratic rights and representation. Anti-racism, reproductive justice, universal housing, access to healthcare, ending police brutality, anti-imperialism, and every other concern of left-wing organizations all rise from the eternal truth that every individual should have agency over their life. And because we all live beside one another in a society rife with conflicting goals, causes, effects, and interests, democracy is the only way for a society to make decisions.

Opponents often criticize Socialists as merely being anti-establishment ideologues, doing the opposite of whatever mainstream America wants. Nothing could be further from the truth. Every time a woman is forced to give birth against her will, or a Black motorist is assaulted by the police, or a Pakistani child is killed in a drone strike, it is a crime not only against the victim’s personhood but their inalienable birthright to decide the path of their lives.

Democracy, both economic and political, is the beating heart of Socialism. But just as the human heart pumps blood to the extremities, Socialism’s heart emboldens the fight against infractions of justice, no matter what form it takes.

Nowadays, terms like “Socialism,” “Marxism,” “free markets,” and “Capitalism” are shouted from political podiums and into TV cameras so flippantly that we’ve taken them as monikers for “good” and “bad.” Reducing these terms into the feelings they invoke is a mistake in dire need of correction. Next time you hear a politician, pundit, or friend use “Socialism” as a proxy for “bad” or “free market” to mean “something we like,” probe their thinking. Why did they decide to use that term? What would be the effect of that policy? Would it create a more democratic, fair world? If the answer is “yes,” then there’s a good chance the mark of “Socialism” is a false shield, used to scare off those who would benefit from the policy’s implementation.

Remember, Socialism and Capitalism are not “teams” to be blindly fought for. They are factual descriptions of socioeconomic systems, comprised of the relationships between people and their workplaces. Capitalism is economic tyranny. Socialism is economic democracy.

What do you think about my thesis, that socialism is economic democracy? Do you think it’s right or wrong? Share your thoughts in the comments.

For those of you who are relatively new to socialism, how does the notion of Socialism = Democracy mesh with your previous understanding of it? Do you agree with it? Or disagree?