[Transcript] Catholicism is my 'Why.' Marxism is my 'How' — An interview on Faith and Socialism with Southern Catholic Worker

Also, we make fun of J.D. Vance.

This is a conversation with Alex, also known as Southern Catholic Worker, a prominent online advocate for Catholic-inspired Marxism. I’ve followed Alex for a while, and can confidently say he’s the only Catholic Marxist I’ve met. As this is an uncommon ideology, I wanted to hear how his unique synthesis of faith and politics came to be. We talked about reconciling faith and Marxism’s anti-religious history, the Catholic Worker Movement, how the teachings of Jesus were warped to support an anti-immigrant, anti-poor, pro-imperialist conservative politics, the late Pope Francis and the new Pope Leo, and how much J.D. Vance sucks. (Spoiler: a lot).

This transcript has been editted for brevity and clarity. You can hear the extended conversation in the audio post here.

Enjoy — Joe

JoeWrote: I'm here with Alex, also known as Southern Catholic Worker on Instagram. Can you start by introducing yourself to the readers?

Alex: My name is Alex. I'm originally from Savannah, Georgia, and I moved to New York, which is one of the reasons I created my account. Originally, it was ‘Southern Marxist’ and now it's ‘Southern Catholic Worker.’ I worked in restaurants in Georgia, where people were fairly conservative. Social media was a place for me to discuss my politics, meet like-minded people, and learn.

JW: As you mentioned, in the United States, Christianity and Catholicism are traditionally aligned with conservatism. I haven't met any Catholics who consider themselves Marxists. How did you end up in a different place politically than most American Christians?

A: I loved my parish growing up, but it was also still fairly conservative, which was alienating. I went through an atheist phase for a while. By the time I graduated from college, I had moved towards Marxist politics. Coming back to the Church was about moving past the idea of the Church being overly conservative, which was a key step in my discovery of Latin American liberation theology. And with the new Pope and with Pope Francis, we're seeing the Catholic Church standing against the current administration in many ways.

“Catholicism is why I believe these things, and Marxism is how I want to implement my beliefs in society.”

JW: Marxist projects have traditionally been atheist. I’m thinking of the Soviet Union. When the Bolsheviks came to power, they criticized the Orthodox Church as an instrument of the Tsarist imperialist government that was propagandizing people against their interests. How do you reconcile your faith with Marxist values when historically the two have been at odds, at least in some strains of Marxism?

A: To bring about my ideas of Christian social justice, as Marx said, “Previously, philosophers just interpreted the world. Now we're trying to change it.”

Catholicism is why I believe these things, and Marxism is how I want to implement my beliefs in society. Politics is about asserting what you value in your society. I believe that everyone has a right to shelter, to food, to healthcare, and all these things are rooted in my faith that we're all children of the same God. It’s the same thing with protecting the environment. Not only are we connected to other humans, but we're also connected to all of God's creation. People should have the right to access basic necessities, and we should also take care of the environment and animals. Marxism is the best tool I've found for analyzing the world and figuring out what the problems are and how to change them.

There have been Marxist experiments, such as the Soviet Union, where the church is largely at odds with the revolutionary project. However, there are also numerous experiences in the 20th century, particularly in Latin America, where Marxists and Christians engaged in dialogue. For me, a big part of liberation theology is that the oppressed can make their own theology. They can engage with the Bible themselves and use it to reflect on their daily lives and the world around them, and then discuss how to change structures of oppression. After all, the majority of Catholics in the world are not in Europe and the United States; they're in the global south. The Catholic Church is growing fastest in Africa. To me, the question is how do we engage with those people in a way that's understanding of their faith and in a way that allows them to take control over their faith and agency over their faith rather than trying to necessarily break them away from it.

JW: I like what you're saying about Latin America. I've always thought Marxism has the same pitfalls as religion, where people get too caught up in debating what is the ‘true’ version: What is the true Islam? What is the true Christianity? What is the true Marxism? And then you get Catholics fighting Protestants, Sunnis fighting Shias, and the Sino-Soviet split. It’s great to hear that, despite the Soviets' atheist approach to Marxism, Latin America has chosen a different path, and it’s been highly beneficial for them.

You mentioned earlier you're a member of the Catholic Worker Movement. What is that? And why is Catholicism focused on uplifting the working class?

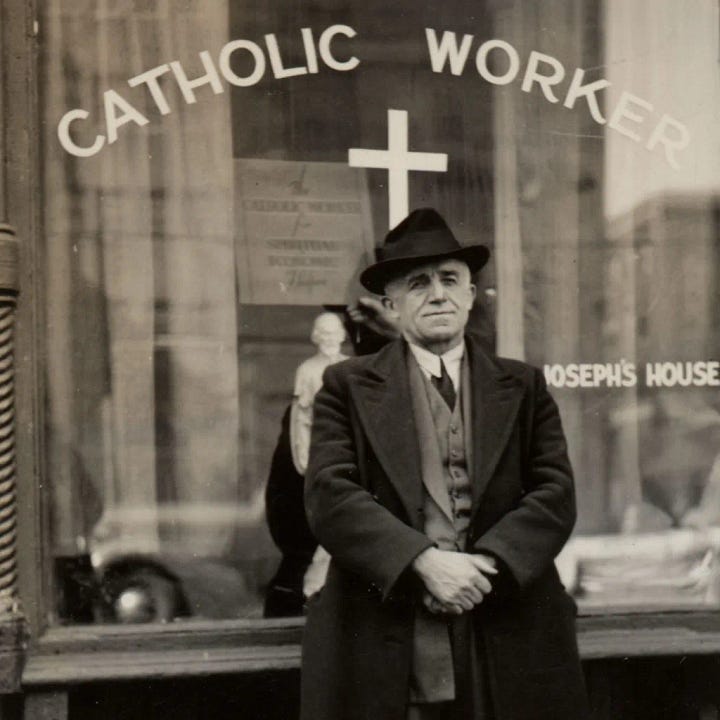

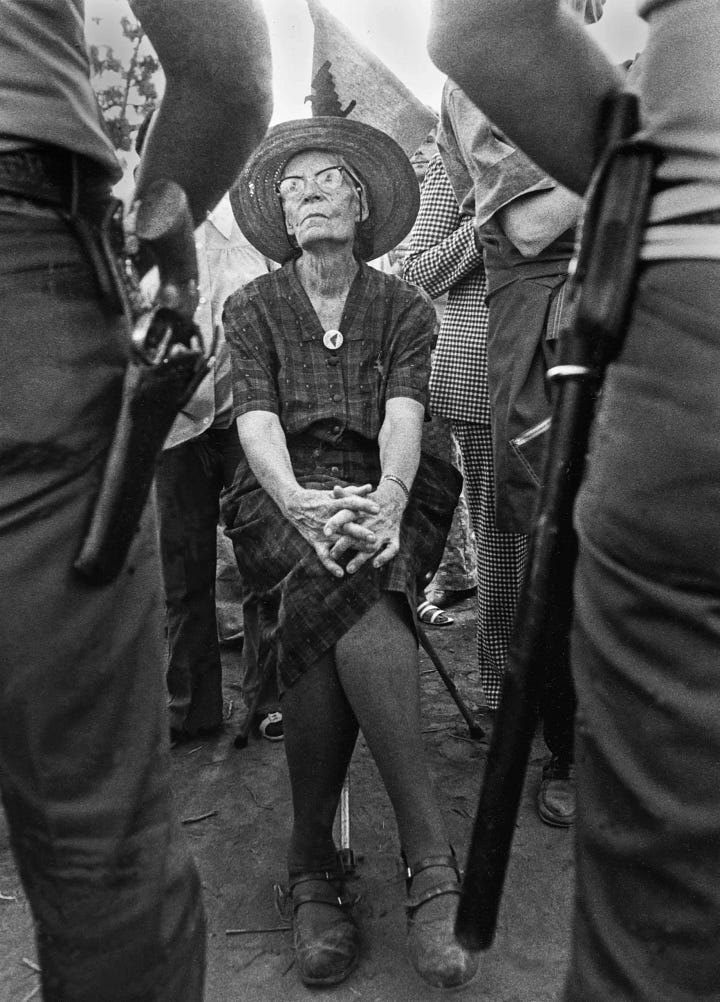

A: The Catholic Worker has houses all over the world. It was founded by Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day in 1933, during the Great Depression. Originally, it was started as a newspaper, but it also expanded into hospitality houses to serve food and coffee to people who needed them. And we still do that. We serve 100 to 150 people every day at our soup line.

Another focus, which comes from Peter Maurin, is returning to the land. Maurin said, 'You can't have a proper society without proper respect for the soil.’ We also have a farm in upstate New York, with the goal of growing nutritious food and utilizing it from a sustainable farm that’s run and serves the people.

JW: That's fascinating. It really speaks to your earlier point that Christian social justice, socialism, and communism go hand in hand. You start by passing out food, and then, of course, you ask, 'Why do we have to pass out food?' ‘Why do these people not have food for themselves?’ And now you’re addressing systemic issues.

Returning to the issue of conservative Christianity, I'll never understand how American Christians can support deportations, low taxes on the rich, or Israel's occupation of Bethlehem, the birthplace of their prophet. In your opinion, why do so many American Christians promote politics in direct opposition to their religion’s espoused beliefs of charity, openness, and forgiveness?

A: Catholics have a joke, ‘There's no length that conservative Christians won't go to miss the point.’ A lot of it goes back to colonization and slavery because religion was used as a superstructural justification for white supremacy, particularly to justify enslavement.

There are two strands in the church. One is aligned with conservative values, the government, and the powers that be, because that's an easier position to take. I think a lot of that comes from Constantine, who converted the Roman Empire to Christianity. The empire co-opted the church to justify the divine right of kings and imperialism. And many Christians still believe that.

But then there’s the other strand, folk Catholicism and folk Christianity, that inspired a lot of rebellions. For example, Nat Turner, who led the slave revolt in Virginia. He was a Baptist minister, but there were also Southern Baptist white ministers who advocated slavery as a positive. They even made slave Bibles that removed any mention of liberating slaves.

Like others, the Catholic Church encompasses a wide range of views, so it’s not entirely conservative. There are conservatives, but we also have the Catholic Worker and the Sanctuary Movement. And there are many parishes like the one I attend here in New York, called St. Francis Xavier, which is very welcoming to the LGBTQ community.

“I have struck for liberty. If I die, I shall die in the glory of the Lord.” — Nat Turner

JW: I'm confused by someone like J.D. Vance and the Catholic Supreme Court justices. They claim to be Catholics, but it looks like their only concern is to help Donald Trump and the Heritage Foundation promote a reactionary agenda. So I’m curious how you see figures like that who claim Catholicism and then actively create a society antithetical to its teachings?

A: A lot of conservative Catholics hate Vatican II, which made the Church less traditional. It moved away from doing mass in Latin towards the native language, and the priest is supposed to face the congregation (as opposed to facing away) when he consecrates the Eucharist. I consider people like J.D. Vance a nerd. As my dad always said, they’re obsessed with pomp and circumstance.

Many conservative Catholics disliked Pope Francis because he focused on involving the laity (common Catholics) for feedback. He particularly wanted to hear from people who had been ignored throughout the church's history. Francis was cool. He’s a complicated figure relating to LGBTQ issues because he used right-wing terminology when talking about gender ideology. But then he was also very supportive of outreach to queer Catholics as well. He approved of Father James Martin's Outreach Catholic ministry, which engages the LGBTQ community. I think that's the reason that conservatives didn't like him.

Specifically, I've disliked JD Vance ever since Hillbilly Elegy came out. If you listen to Appalachians, they clocked him as a snitch who was exploiting his connection to Appalachia to advocate for hedge fund billionaires such as Peter Thiel. Converts like him are attracted to the historic trappings of Catholicism, like the architecture and all this other stuff, so they tend to skew conservative.

JW: You mentioned Pope Francis. I'd love to hear how you view his legacy. As you said, it's imperfect from a leftist, social justice perspective. However, and correct me if I'm wrong, but I believe he was the first pope to permit priests to bless same-sex couples. How do you view the late Pope's legacy?

A: I fuck with Pope Francis. I thought he was cool. His two most important legacies are, first, contributions to ecology. He wrote Laudato si’ and Laudate Deum, which are pretty anti-capitalist and attack the idea of accumulation and infinite economic growth. He also promoted the idea that we're all connected, particularly to nature and animals. He said, ‘We're not here to dominate. We're here to be companions with them.’ I really liked that.

The fact that he chose the name Francis was cool. St. Francis of Assisi came from a rich merchant family in Venice, and he renounced all of his wealth to go live among the poor. The legend is that he would give sermons to animals, and they would understand him. Francis picked the name because he was focused on humble, lowly, and standing in solidarity with the poor .

The second thing Francis did was the Synod on Synodality, which asked people what they think and used that to shape Church policy. Getting input from the laity and opening up to previously-ignored communities was important.

I think those are two of Pope Francis’ lasting contributions. And Pope Leo is a continuity pick because he was very supportive of those ideas.

JW: It’s encouraging that the Cardinals chose to continue that tradition and didn’t fall into a reactionary backlash. What do you take as the significance of electing the first American Pope in history?

A: Bishop Baron, who is Trump’s advisor, said the only time they would ever elect an American pope was if the US were in political decline. Leo’s election is a message to Trump, particularly on immigration. So far, my boys’ come out swinging! In his first Sunday address, he talked about ending the war in Gaza. Someone asked him, ‘Do you have any message for the United States?” And he said, ‘Many.’ That’s a cool response.

But Leo has some of the same problems as Francis. Some past statements about LGBTQ issues are not good. But my biggest problem with Leo and with Francis is abuse within the Church.

Francis covered up sexual abuse, and he should have faced repercussions for that. And Leo has been accused of protecting people who have abused parishioners. The Church has eliminated some of the problems, but when victims speak out, they need to be centered. Abuse is a huge problem, and these things need to be taken very seriously. The church can't just say, ‘We’re Christian, so we forgive the abusers.’

JW: Over the past year or so, I’ve been toying with the idea of reconnecting with the Catholic faith. I was raised Catholic, but I've since lapsed. I'm not sure if my renewed interest is because the world is in such a dark place and I want something to believe in, or because I’ve seen the teachings of Jesus as synonymous with my progressive values. I think I speak for a lot of people when I say the Church’s protection of sexual abuse and socially conservative positions on gender, abortion, and gay marriage are holding me back. What would you say to someone like me who shares the values you've spoken about in this interview, but is hesitant given conservative positions or abuse scandals?

A: A lot of times, Catholics will defend the church. I don’t do that. The most important thing for Christians is to listen, provide, and show solidarity with victims so they can receive justice through the Church.

If you’re considering coming back to being Catholic, my advice would be to explore theology and find something that resonates with you. For me, a big part of my return was discovering Saint Romero, the archbishop in San Salvador who the El Salvadoran government assassinated for speaking out for the poor.

Then find a suitable parish. 99.9% of your interaction with the Church will be through your local parish, so find one you feel comfortable in. When I came back, I was living with some queer friends, and I don't want to go to any church where friends wouldn't be welcomed.

Even though we think the Church has this orthodoxy that doesn't change, it does. Personally, I want to see the Church change, such as accepting queer people, being open towards women's health and women's autonomy, and giving land back to the indigenous communities the Church stole it from. For these changes to happen, we need more people within the Church to push for them.

JW: That's very inspiring. Before I let you go, this last question is on everybody's mind. Did JD Vance kill Pope Francis?

A: Probably. Pope Francis was probably so frustrated after meeting him. He thought, ‘I need to go. Like, take me now, God.’

As always, please click the ❤️ if you enjoyed this interview, and don’t forget to subscribe so future ones are delivered straight to your inbox. If you enjoy JoeWrote, even sometimes, please consider upgrading to a premium subscription. It costs one cup of coffee a month, gets you access to exclusive interviews, and ensures I can continue doing this work. Thanks in advance!

In Solidarity — Joe

Links:

Check out The Catholic Worker Movement

Follow Alex on Twitter

Follow Alex on Instagram

Thank you for posting this, I enjoyed reading it. When it comes to religious groups’ position on social justice and economic issues, a good book to read is called The End of Empathy by John Compton. I’m only a hundred pages in so I’m not sure when exactly the switch to ultra conservative positions happened, but in the late 19th and early 20th century, the religious take on these issues were very liberal, especially during the Progressive Era and the Great Depression. Most of the New Deal policies received very strong support from Protestants, Catholics, and Jews, despite some more conservative voices opposing them (which were of course linked to industry). I’m at about the 1950s, where it was still pretty liberal, but I don’t think the conservative switch happened for at least another decade.

thank you so much for posting this. It made my day!! As a former Catholic who attended Catholic high school I long for the 70s when it seemed like the Catholic Church was moving towards being far more open and inclusive. Pope Francis was moving in that direction, but his age and infirmity made it difficult for him to continue. Hopefully Pope Leo can continue the process to a kind and loving Catholic Church.