200 Years of the Monroe Doctrine

What better time to shred the Monroe Doctrine than its 200th birthday?

Hey folks, if you enjoy my work please support me by sharing this article with a friend, liking it (click the heart emoji up top), and becoming a subscriber, either free or paid. Subscriptions are available at whatever price you can afford.

Thank you for your support. In Solidarity — Joe

On December, 2nd, 1823, President James Monroe delivered his annual address to Congress. In his speech, Monroe articulated a doctrine that would impact American foreign policy for centuries to come. Though it did not take his name until long after his Presidency, the Monroe Doctrine has become a cornerstone of American politics. It has been revised, updated, and implemented by Presidents and diplomats from both parties, used to justify America’s hegemony over the Western hemisphere, and has destroyed more South American lives than we will ever possibly know.

But that was not its intent.

Speaking 200 years ago, President Monroe’s original statements are far departed from what the Monroe Doctrine would become. In his speech, Monroe criticized the imperialism of Spain, Portugal, Great Britain, and other “Old World” (European) nations who sought to control their current and former colonies in Central and South America.

“But with the Governments who have declared their independence and maintain it, and whose independence we have, on great consideration and on just principles, acknowledged, we could not view any interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or controlling in any other manner their destiny, by any European power in any other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States.” - The Monroe Doctrine

Speaking as the head of a nation that only achieved independence from a European power a few decades prior, Monroe’s words are admirable. He praises the rights of South Americans to self-govern and states the U.S. has the right to assist its “southern brethren” in escaping European control. It is not a bellicose speech, as it routinely calls for peace and states the U.S. has no issue with connections between American and European governments, so long as they are mutually agreed upon between the nations in question.

Given this language is far from what we hear from American statesmen, it’s natural for many to assume Monroe was attempting to deceive the world with a facade of self-determination. But I don’t believe he was. At the time, the United States was weak and far from capable of exerting imperialist control over its neighbors, never mind the far away lands of South and Central America. The country had only recently survived the War of 1812 and the crippling British blockade that came with it. And though Americans desired to spread across the continent, expansion into South America would have seemed foolish and impossible.

In fact, Monroe’s speech was welcomed by those currently fighting European colonialism in South America. Revolutionary leader Simon Bolivar looked upon it fondly and invited the U.S. to his 1826 Congress of Panama. Immediately upon hearing Monroe’s words, Colombia and La Plata (modern-day Argentina) requested American protection against Brazil, which was governed by a member of the European Hapsburg dynasty.

But while Monroe’s intent to end European influence over “The New World” was genuine, his Doctrine would ultimately become the basis for U.S. imperialism. As the country grew in size and might, the Monroe Doctrine was refined to fit the U.S.’s objectives, which came to emulate and replace the European desire for colonialism Monroe had rallied against.

The 19th Century

Immediately following its proclamation, the Doctrine was used in line with its original intent. In 1864, the French installed Maximilian I as the Emperor of Mexico after President Benito Juarez suspended the country’s loan repayments. Once the American Civil War ended, the U.S. supplied Juarez’s forces under the basis of the Monroe Doctrine. Backed by the U.S., Juarez soon won the civil war and reclaimed power. The French withdrew their support, and Maximilian’s reign ended.

But in the post-Civil War years, the Doctrine began to be transformed from one of protection to one of control. President Ulysses S. Grant stated that it meant no European power should have a foothold in the Americas, a reversal from Monroe’s belief that the U.S. should remain neutral in agreed-upon governance between New Worlders and Old Worlders. Under the 1880s Arthur Administration, Secretary of State James G. Blain’s “Big Brother” policy stated that the U.S. should lead the Americas and that commercial interests should be shared throughout the Western Hemisphere. Though it seems unimportant, this was a drastic change as it was the first time the Monroe Doctrine explicitly mentioned economic interests. But it would not be the last.

In the final decade of the 19th century, the Monroe Doctrine was put to the test. In a dispute between Britain and Venezuela over land rights, the U.S. invoked the Monroe Doctrine, claiming it gave them the right to mediate border disputes in the Western Hemisphere. Known as the “Olney Corollary” after Secretary of State Richard Olney, this altered the Monroe Doctrine from a position of anti-European influence to one of hegemonic control. By accepting the U.S.’s insistence that it was the rightful mediator of the dispute, Britain admitted the United States was now the chief decision-maker in The New World. Though unknowingly, this elevated the United States to the position of a global superpower, which it still holds today.

20th Century

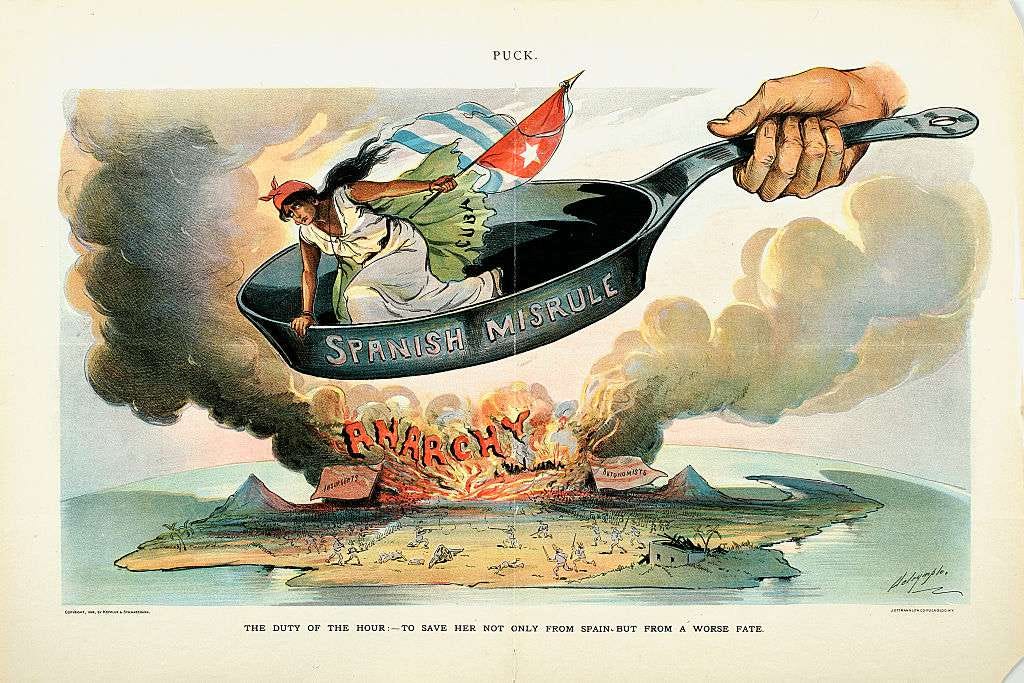

When the Spanish-American War broke out in the spring of 1898, one of its leading proponents was Theodore Roosevelt, who saw Spanish control of Cuba and other Latin American nations as an affront to U.S. power. Three years after the war, Roosevelt assumed the Presidency and issued the Roosevelt Corollary, which stated the U.S. had a right to intervene to stop “unrest, wrongdoing, or impotence” in the Western hemisphere.

Chronic wrongdoing...may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation… “And in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power." - The Roosevelt Corollary

The Roosevelt Corollary was the most drastic change to the Monroe Doctrine, as it stated the United States could intervene in South America at will, a direct contrast to the anti-colonial message Monroe had laid out eighty years prior. And these were not hollow words, but a forceful change in U.S. policy that greatly expanded its imperial aims.

It was around the time of the Roosevelt Corollary that the United States took a new approach to foreign policy. As European control was in retreat, U.S. imperial and financial interests saw the opportunity for new territories and their markets. The Corollary offered a moral justification for American expansion, bastardizing Monroe’s original intent from one of national independence to one of American hegemony.

Immediately following the Spanish-American War, America ignored the wish for Phillipino independence and annexed the archipelago nation. Philippine guerrillas fought the American occupiers until 1913 when they were finally defeated. In 1901, the Senate approved the Platt Amendment the treaty between the U.S. and newly independent Cuba. Despite having a previous provision that the U.S. would not occupy the island, the Platt Amendment made Cuba a de facto protectorate of the United States. Charles Magoon, a U.S. statesman, was appointed to govern Cuba. He did so from 1906 to 1909.

While the Monroe Doctrine would not explicitly adopt the interest of capital until the passage of the Lodge Corollary in 1912 (this expanded the Doctrine to include corporations owned by foreign countries), the Roosevelt Corollary was largely used to make way for capitalist expansion in Latin America.

In 1903, the Columbian government rejected the U.S. proposal to purchase the land that would become the Panama Canal (Panama was still a part of Columbia at the time). Wanting to create the long-desired canal that would make international shipping cheaper, President Roosevelt sent warships and troops to assist a small breakaway rebellion in Panama. Before Columbia even realized it, U.S. Marines were fighting alongside Panamanian rebels. The Columbian forces were no match for the well-equipped Americans. Soon, Panama was declared independent. Roosevelt quickly signed a treaty for the canal land with the new Panama government. Construction on the Panama Canal began soon after.

In 1911, The United Fruit Company (which would later become Dole) purchased 15k acres of farmland in Honduras. Conspiring with the Honduran ex-president and American mercenary captain Lee Christmas, the group overthrew the government, which was seen as hostile to foreign capitalists. The U.S. government did not intervene per se, but the State Department permitted the coup on account that the deposed ruler was friendly with Great Britain, a supposed violation of the Monroe Doctrine.

But all these episodes were only the beginning. Between the start of the 20th century and World War II, the United States invaded, occupied, or intervened in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and Mexico, all under the justification of the greatly altered Monroe Doctrine. These expeditions were often brutal, such as when the Marines killed thousands of Haitians through forced labor. And though the Doctrine was only used in South America, it gave the U.S. an appetite for foreign adventure. During this time period, U.S. troops were sent all around the globe, from China, to Europe, and even to Siberia to fight against the Russian Bolsheviks.

But what is even more telling than where the Monroe Doctrine was invoked is where it was not invoked. In 1902, European powers blockaded Venezuela for refusing to pay debts. Roosevelt allowed the blockade to go on uninterrupted, arguing the Monroe Doctrine was not a binding contract to protect, but the option to intervene. This was a key turning point in the life of the Monroe Doctrine, as it showed the U.S. had no interest in the doctrine’s original intent — protecting Latin America from European colonialism. Instead, it showed the U.S. was only interested in using the Doctrine as an excuse to increase its own power.

America has always been an empire, as every inch of its land was conquered from indigenous nations. But the Roosevelt Corollary was its second evolution. As soon as it was announced, the United States began using the Corollary, and therefore the underlying Monroe Doctrine as a blank check for imperialism. While it began this process before World War II, it wasn’t until the Cold War period that this project was taken to the extreme.

The Cold War

Following WWII, the US launched numerous invasions and incursions around the world to combat the perceived threat of communist expansion. While the CIA and American military operated in every region, many of these operations took place in South America, wanting to drive communism from “America’s backyard.” As they had done before and would do again, American politicians altered the Doctrine from its intended purpose of preventing European imperialism in the Western Hemisphere to one of American hegemony.

A few months before the Cuban Missile Crisis, President John F. Kennedy invoked the Doctrine when condemning relations between Moscow and post-revolution Cuba.

The Monroe Doctrine means what it has meant since President Monroe and John Quincy Adams enunciated it, and that is that we would oppose a foreign power extending its power to the Western Hemisphere and that is why we oppose what is happening in Cuba today.

As he would do months later during the Missile Crisis, Kennedy was intentionally warping the doctrine from its original meaning. While Monroe had specifically stated the Doctrine did not apply to mutually agreed relationships between Latin American and European countries, Kennedy and his advisors claimed the Doctrine refuted any relations between sovereign nations, even those that were agreed upon. In this case, it was a mutual relationship between Cuba and the Soviet Union. This was a massive leap forward for both the Monroe Doctrine and the United States. No longer was the U.S. saying it was the “big brother” of Central and South America, protecting smaller nations from powerful adversaries. Now, the U.S. was stating it was the overbearing parent — able to decide for other nations which relationships they were and were not allowed to have.

But of all the illicit acts the United States committed during the Cold War, none were more pervasive than Operation Condor. Officially beginning in 1975, Operation Condor was an international conspiracy led by the CIA to combat communism and other leftist sentiments throughout the Western Hemisphere. The operation was run in partnership with the right-wing governments of Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, Brazil, and Peru and was approved by three US Presidents: Ford, Carter, and Reagan. Targeting anyone and everyone who even smelled of leftism, these governments allowed the CIA to train, equip, and direct both governmental forces, such as the national police and militaries, and paramilitary organizations in a campaign of state terrorism throughout the South American continent.

Acting with legal impunity and backed by the most powerful military in the world, these groups carried out assassinations, torture, kidnappings, and massacres at will. Everyone from revolutionaries, to union leaders, to peasants, to nuns was targeted. The discreet nature of the operations makes the final death count hard to gauge, but the consensus estimate hovers around 60,000 deaths and up to half a million illegal imprisonments and disappearances. The most infamous episode of Operation Condor was the Iran-Contra scandal, in which President Reagan sold weapons to Iran to finance the Contra rebels in Nicaragua. The political scandal arose after Operation Condor had been formally ended, but still, it was defended by the CIA as a reasonable interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. Though the Sandinistas established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union after they came to power in Nicaragua, the Sandinista movement was organic. It came from the will of the Nicaraguan people, not an imported Soviet influence. In arming the Contra terrorists, the United States was not combatting an aggressive European power, but acting against the wishes of the Nicaraguan people. Much like Kennedy’s words two decades prior, the justification of the Iran-Contra scandal and Operation Condor under the Monroe Doctrine shows how it had become a diplomatic ship of Theseus — its original provisions had been removed and replaced, that one has to wonder if it was really “the Monroe Doctrine” anymore.

As the Cold War and the 20th century came to a close, many assumed the Monroe Doctrine would slip into obscurity. The specter of a communist horde overrunning the world was no longer a fear of the political establishment, and even before 9/11, the Pentagon had begun eyeing the Middle East as its next stomping ground. But, die the Monroe Doctrine did not.

21st Century

Though the imperialist form of the Monroe Doctrine is alive and well today, there was a brief moment in which it looked like the United States might leave the Doctrine in the historical dustbin. In 2013, Secretary of State John Kerry announced to the Organization of American States that “the Monroe Doctrine is over.” He spoke of cooperative relationships between the United States and its South American neighbors, discarding the previous belief that the U.S. was the ruler of the hemisphere. Though widely celebrated, the relief did not last.

Almost as soon as he took office, President Donald Trump accelerated his aggressive campaign rhetoric against Latin America. He repeatedly discussed aggressive policies, such as bombing Mexico and invading Venezuela. While Donald Trump likely has no actual beliefs about the Monroe Doctrine, those around him do. Trump’s CIA Director Mike Pompeo, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, and National Security Advisor John Bolton all praised the Monroe Doctrine and stated it was still in effect. Bolton even praised it at a meeting of Bay of Pigs veterans in Florida, a bizarre statement considering the USSR is no longer around. Thankfully, no South American invasion came into play, but Trump’s policies were clearly those of a government that believed it had an innumerable right to dictate the lives of those who shared its hemisphere. He revoked the right of refugees to claim political asylum in the United States, forcing other nations to bear the brunt of political migration. Venezuela was placed under crippling economic sanctions, worsening its already-bad economic downspin. Mexico was routinely threatened with economic sanctions with little to no explanation, and many other Latin American countries found themselves on the end of a 21st-century “gunboat diplomacy” — do what America wants, or else.

While no invasion or airstrike came during Trump’s four years in office, his rhetoric can not be seen as isolated. Yes, he was uniquely crude and racist, but his outlandish ideas found footing because the American political establishment had spent the prior century viewing Latin America as a possession of the United States.

In many ways, the history of the Monroe Doctrine provides a perfect summary of American foreign policy. Though I would not call President James Monroe a peacenik (like all pre-modern presidents he enabled the genocide of Indigenous nations and oversaw the continuation of slavery), the words of his original doctrine leave no doubt about his intent — he desired the Western hemisphere to exist without domination from the all-mighty European powers, and was willing to use American resources to protect that idea.

But, as the world changed and hegemons fell, what had been an anti-imperialist doctrine quickly transformed into one that justified America imposing control over the Western Hemisphere, and eventually, the entire world. The Monroe Doctrine was born against European colonialism, then changed to oppose any European influence, and then modified again to give the United States parental rights over the entire hemisphere. In just over a century and a half, what started as an arguably righteous belief was used to justify the overthrowing of democracies and the arming of Contra death squads.

But like every other Empire that has come before it, America could not kick the colonialist habit. Our foreign interventions began by sending troops and financiers south, but soon they turned east and west. Today, the United States has over 800 military bases around the globe, controls the global monetary supply through the Bretton System, and continues to dictate which governments are permitted to exist and which should be toppled, the will of their people be damned.

At every instance of American imperialism, the Monroe Doctrine has been there, offering a flimsy justification for why it’s okay for the U.S. to topple democracies and support death squads. And though I find James Monroe’s original intent admirable, two centuries of corruption have turned the Monroe Doctrine into a vile manifesto.

Now that we know its full effect, the Monroe Doctrine should be discarded, once and for all.

And now America has decided to topple its own democracy and wage war against its own people. Let's call this one the Censorship Corollary? Or let's go back further and call it the 9/11 Corollary?