Irish Americans Are Uniquely Positioned to Dismantle White Supremacy

From being excluded to welcomed, our history shows the folly of xenophobia and bigotry.

Happy Saint Patrick’s Day! ☘️

While today’s global celebrations feature the liveliest aspects of Irish culture, it’s essential to remember Erin's most important characteristics: steadfast opposition to domination, refusal to be erased by colonization, and unwavering solidarity with the world’s oppressed. Though Ireland enjoys a modern, peaceful existence, the tiny island nation has not forgotten its history.

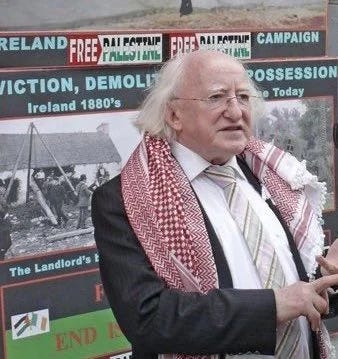

After surviving eight hundred years of British imperialism, the Irish people repeatedly stand in solidarity with Palestine, which is currently enduring settler colonialism and occupation all too familiar to the Irish memory. After being outlawed by the British, Irish language speakership is rising,1 and polls show increasing support for reunifying the island, even among Protestants.2 There’s even a Belfast-based rap group, Kneecap, whose Irish language songs are topping charts around the globe.

While the nation does not share my exact political preferences (a centre-right coalition governs it, and Ireland has long functioned as Europe’s corporate tax haven), it’s clear the Irish have not forgotten their identity as a colonized nation. And how could they? The very fact that their most-spoken language is English is a perpetual reminder that their neighbor tried to stamp them out of existence. The population still hasn’t recovered from The Great Hunger. There are seven million people in Ireland today, compared to eight million in 1841, before the British genocide. While modern Ireland is a developed nation that is not too different from any other European country, this collective past clearly informs its current identity and worldview.

Unfortunately, the same can not be said about the Irish diaspora here in America.

While the Irish American identity was once a unique culture, being an Irish American is now no different than being any other White American. There’s no anti-Catholic discrimination; having an “O” or “Mc” in your last name doesn’t get your resume thrown in the trash, and a man with my mother’s family name sits on the Supreme Court. (I have no relation to Brett Kavanaugh. Or, at least I hope I don’t.) Given the assimilation, it’s no surprise the notion of Irish American heritage has drifted to the conservative right. Trump recently signed an executive order declaring March “Irish American Heritage Month,” boasting the group “voted for him in heavy numbers.”

While there’s no evidence to confirm or dispute this claim, former Trump spokesperson Sean Spicer described why he agrees with this assessment:

"[Irish Americans] have gone from worker to owner in the last couple of generations. They see the issues and policies Donald Trump and the Republican Party champion as more in line with their values now as someone who owns a company or is higher up on the corporate ladder." 3

And to be honest, I think Spencer is right. Once marginalized, White-skinned ethnicities are free to climb the social ladders of the United States. However, I don’t believe this is because America has lost its racist and xenophobic strains but because of the ever-shifting, ever-nonsensical structure of White supremacy.

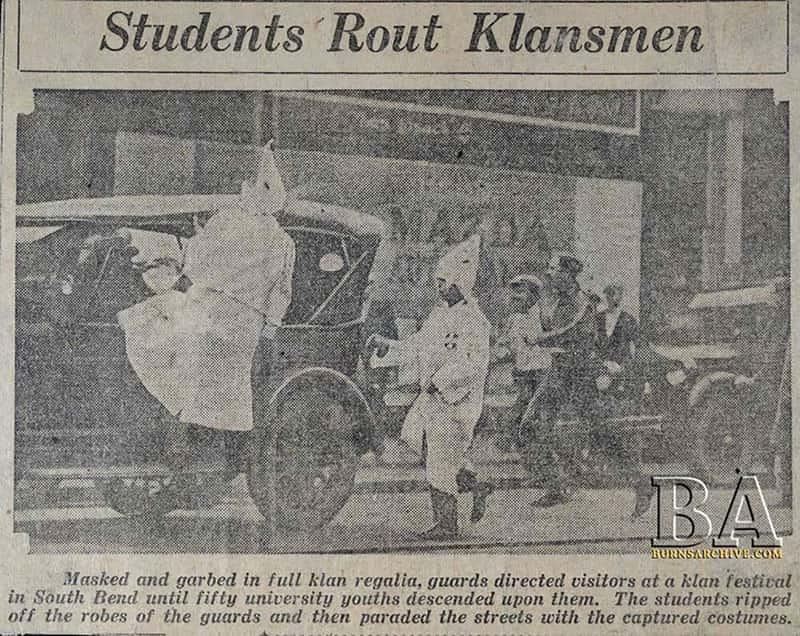

Before the mid-20th century, Catholic European emigres faced systemic oppression in the United States. Italian, Polish, and Irish Americans were denied jobs, attacked by hate groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, and enclosed in the lower, poorer sections of society. Yet, that is not the experience of Irish Americans today. So, what changed? To put it simply, the Irish became White.

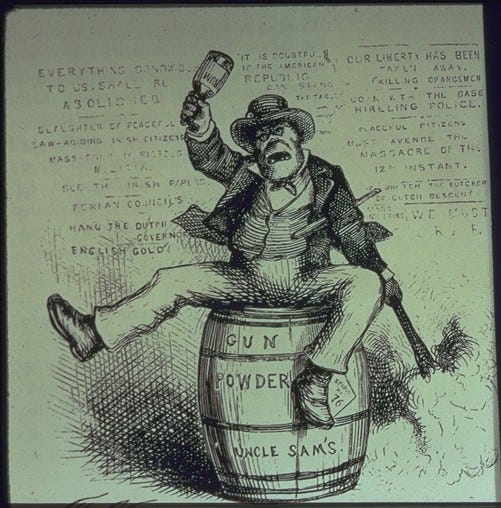

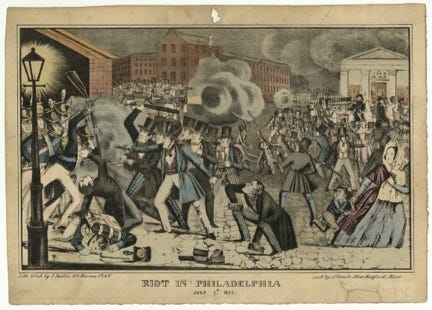

Every time a young woman holds a sign at a protest that says something like “Race is a Social Construct” or “Dismantle White Supremacy,” the online right has a field day. They mock and deride the advocate, insisting these ideas are only viable in the intellectual honesty of a drugged-up drum circle. However, as the unique experience of Irish Americans shows, such statements are accurate. Throughout American history, “Whiteness” hasn’t been a physical descriptor but a term for social acceptance. I’d argue that while “being White” is an observable trait, the concept of “Whiteness” only exists thanks to its counterpart — the feared “other.” Black, Indigenous, Latino, and immigrant communities have continuously occupied this space in the minds of reactionaries, but the “other” didn’t always have non-White skin. The Know-Nothing Party was effectively 19th-century QAnon, claiming the Pope was sending Irish and Italian Catholics immigrants to America to take over the country from within.4 In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first time federal law prohibited entry into the country based on ethnicity.5 Entire political parties arose in opposition to immigrants with White skin, and racial terrorism was common.

Yet, a mere century later, anti-Irish discrimination was gone. The same cannot be said about anti-Black discrimination. These vastly-different American experiences are due to, as our aforementioned hypothetical protestor stated, White supremacy being a social construct. It was created by the ruling class to preserve their social position, and, therefore, could be altered per their immediate political objectives. As Black Americans were liberated from slavery and struggled for civil rights, White ethnicities that were once excluded from America’s in-group were welcomed with open arms. Skin color, not religion, became the defining trait of Whiteness to present a united front to “defend the White race.” Even the concept of a “White race” shows the absurdity of racial supremacy, as differences between Protestant Englishmen and Catholic Irishmen were forefront for the vast majority of modern history. They were only lumped into the same “race” when they were needed to combat Black civil rights.

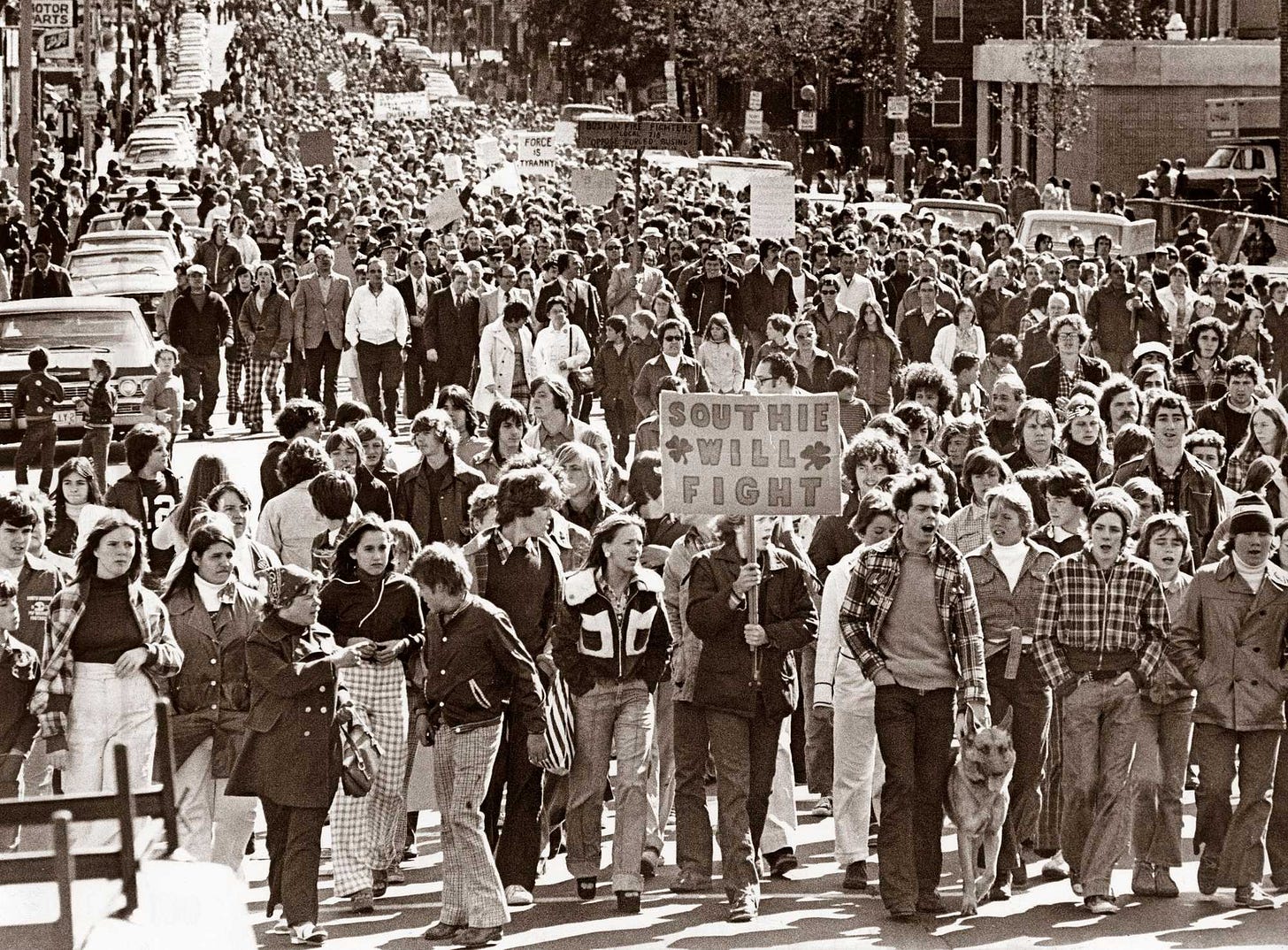

Unfortunately, Irish Americans were happy to participate in racial segregation as long as it meant they were no longer the bottom rung on the ladder. Past and present, Irish surnames are overrepresented on police uniforms, and race riots targeting Black neighborhoods are not uncommon. When Massachusetts desegregated public schools in 1974, the South Boston, the iconic Irish Catholic neighborhood, erupted in protest.

If given the chance to talk to any of these fellow Irish Americans, regardless of whether they were a factory worker in 1880s New York, an anti-busing protestor in 1970s Boston, or one of the “many” Irish Americans who voted for Trump in 2024, I would say the same thing: Do you guys really not see how this works? The family history you love to recall is one of great suffering. Your ancestors braved the Atlantic on overcrowded coffin ships, endured domestic discrimination, and survived racial terrorism. The British tried to genocide your great-great-great grandfather, and the Klan lynched him for walking down the wrong street. Clearly, you of all people should see how xenophobia and bigotry are tools to keep working Americans mad at each other and preserve the position of those in power.

I cannot fathom how one can recount the tales of Irish refugees, hunger pulling their skin pulled taut over cheekbones and not immediately sympathize with modern immigrants. (“bUt mY iRiSh aNcEstOrs cAmE LeGALly” — Fuck off. Ellis Island let in anyone who could swing a hammer.) How can you fly the tricolor outside your home, a flag long-outlawed by British occupiers trying to erase the Irish national identity, and not draw parallels to Palestinians, who are also barred from flying their national banner by the Israeli occupation?6 While Catholics have celebrated the Patron Saint Patrick for centuries, the first modern Saint Patrick’s Day celebration was in New York City in 1851, during the height of anti-Irish discrimination. Today isn’t a joyous holiday celebrated around the globe because nations were happy to welcome Irish refugees. Quite the opposite. The holiday rose to international prominence as a defiance to existing White supremacy structure. Through their celebration, Irish immigrants defied the xenophobes who attempted to erase them, stating, “We are here, but we will not be erased. We are proud to be Irish, even when you tell us to be ashamed. We will not let you erase us.” That’s why we have Saint Patrick’s Day. The parades and festivities are just an extra.

Growing up, I was always told my family was 100% Irish. As that’s a common claim, I assumed it was a myth. But last summer, my friend signed up for Ancestry.com, traced my lineage, and wouldn’t you know it, my family’s lore was genuine. Every one of my ancestors was a refugee fleeing the Great Hunger between 1840 and 1870. (My mom’s side moved to Britain for a few years before immigrating to the U.S., but hey — nobody’s perfect.) Since then, I’ve been thinking a lot about the historical path I exist upon. Today, I’m no different than any other White guy. I face no linguistic or ethnic barriers, and countless studies have shown that my White-sounding name is more likely to be chosen from the resume pile than Black and Hispanic surnames. But it wasn’t always that way. Centuries ago, my starving ancestors made perilous journeys similar to those endured by today’s immigrants fleeing chaos and oppression in hopes of a better life. When my grandfather passed, we found donation receipts to Irish Republican groups tucked away in his closet. While Irish sovereignty is now taken as a given, such activity would have been considered “supporting terrorism” back then. That’s the same claim the Trump administration used to justify the kidnapping of Mahmoud Khalil, a pro-Palestinian organizer abducted by America’s new secret policy.7 That same treatment could easily have been endured by any Irish American who advocated for Irish independence during the Irish Revolutionary Period. The Irish and Palestinian national struggles are as close as a one-to-one as we can get in the real world, yet many Irish Americans support one but condemn the other. Joe Biden, who loudly champions his Irish heritage, gave unlimited armaments to Israel during his presidency. Even when the Irish Prime Minister equated the Palestinian and Irish national struggles at last year’s White House Saint Patrick’s Day celebration, Biden refused to see the truth.

While I take pride in my ancestry, I don’t believe the contemporary Irish American identity should resign itself to drinking green beer and recalling tales of the past. It must look forward, applying the lessons of our unique ethnic experience to contemporary struggles. The Irish American experience proves that xenophobia, colonization, and White supremacy are artificial. They were created by the powerful to preserve social and economic status quos, modified to survive the advancement of society, and, like all human creations, can be eradicated. And I can’t think of anyone else who should work to dismantle bigoted systems than the descendants of those who suffered under them.

While this was a heavy topic, I hope you enjoy your holiday. There’s not much to celebrate nowadays, so time with friends and family is something we all need. If you found this article insightful, please ❤️ it and subscribe to support my work.

Happy Saint Patrick’s Day!

In Solidarity — Joe

https://imminent.translated.com/ireland-back-to-irish

https://www.irishtimes.com/ireland/2025/02/07/support-for-irish-unification-grows-but-unity-vote-would-be-soundly-defeated-in-north-poll-shows/

https://www.rte.ie/news/analysis-and-comment/2025/0311/1501358-us-ireland/

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Know-Nothing-party

https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/chinese-exclusion-act

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/01/israel-opt-flag-restrictions-are-the-latest-attempt-to-silence-palestinians-and-reduce-their-visibility/

https://www.politico.com/news/2025/03/16/rubio-defends-detainment-columbia-activist-arrests-00232477

Petition for the immediate release of Mahmoud Khalil who was kidnapped from Columbia University.

https://actionnetwork.org/letters/demand-the-immediate-release-of-columbia-student-pro-palestine-advocate-mahmoud-khalil-from-dhs-detention

This is the post I wanted to write but couldn't. Thank you so much, Ireland forever ❤️ 🇮🇪